Breaking News

We MUST keep talking about this, demand Voter ID. Joe Rogan and Elon Musk on Fraud

We MUST keep talking about this, demand Voter ID. Joe Rogan and Elon Musk on Fraud

Nick Shirley exposes there are 1,200 medical transport companies in Minnesota.

Nick Shirley exposes there are 1,200 medical transport companies in Minnesota.

Trump Explains How The US Really 'Is' NATO

Trump Explains How The US Really 'Is' NATO

Trump Says "Investigation Of California Has Begun" As Surgical Truth-Bombs About Corruptio

Trump Says "Investigation Of California Has Begun" As Surgical Truth-Bombs About Corruptio

Top Tech News

The First Production All-Solid-State Battery Is Here, And It Promises 5-Minute Charging

The First Production All-Solid-State Battery Is Here, And It Promises 5-Minute Charging

See inside the tech-topia cities billionaires are betting big on developing...

See inside the tech-topia cities billionaires are betting big on developing...

Storage doesn't get much cheaper than this

Storage doesn't get much cheaper than this

Laser weapons go mobile on US Army small vehicles

Laser weapons go mobile on US Army small vehicles

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Harvard scientists uncover an exploitable Achilles' heel common to most bacteria

Finding ways to disarm these defenses is a key component of antibiotics, and now researchers at Harvard Medical School have identified a structural weakness that seems to be built into a range of bacterial species, potentially paving the way for a new class of widely-effective antibacterial drugs.

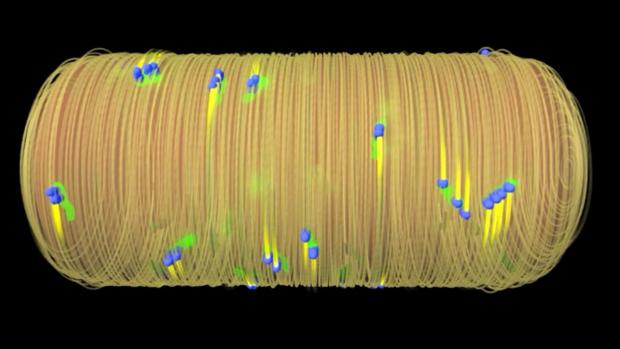

The new study builds on previous research into a protein named RodA. While the protein itself has long been known, in 2016 the Harvard team was the first to discover that it builds the protective cell walls of bacteria out of sugar molecules and amino acids. Since RodA belongs to the SEDS family of proteins, which is common to almost all bacteria, the team realized it was the perfect target for a far-reaching antibiotic. And on closer examination of RodA, the researchers spotted a vulnerable looking cavity on the outer surface of the protein.

"What makes us excited is that this protein has a fairly discrete pocket that looks like it could be easily and effectively targeted with a drug that binds to it and interferes with the protein's ability to do its job," says David Rudner, co-senior author of the study.

To test whether this cavity was the Achilles' heel they were looking for, the scientists altered the structure of the protein in two species of bacteria, E. coli and Bacillus subtilis. These two were chosen because they're well understood and represent the two broad classes of disease-causing bacteria, gram-positive and gram-negative.