Breaking News

US Lawmakers Shmooze with Zelensky at Munich Security Conference...

US Lawmakers Shmooze with Zelensky at Munich Security Conference...

Scientists have plan to save the world by chopping down boreal forest...

Scientists have plan to save the world by chopping down boreal forest...

New Coalition Aims To Ban Vaccine Mandates Across US

New Coalition Aims To Ban Vaccine Mandates Across US

Top Tech News

New Spray-on Powder Instantly Seals Life-Threatening Wounds in Battle or During Disasters

New Spray-on Powder Instantly Seals Life-Threatening Wounds in Battle or During Disasters

AI-enhanced stethoscope excels at listening to our hearts

AI-enhanced stethoscope excels at listening to our hearts

Flame-treated sunscreen keeps the zinc but cuts the smeary white look

Flame-treated sunscreen keeps the zinc but cuts the smeary white look

Display hub adds three more screens powered through single USB port

Display hub adds three more screens powered through single USB port

We Finally Know How Fast The Tesla Semi Will Charge: Very, Very Fast

We Finally Know How Fast The Tesla Semi Will Charge: Very, Very Fast

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

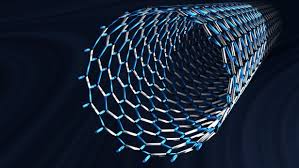

Laser-activated nanotube skin shows where the strain is

Whether they're in airplane wings, bridges or other critical structures, cracks can cause catastrophic failure before they're large enough to be noticed by the human eye. A strain-sensing "skin" applied to such objects could help, though, by lighting up when exposed to laser light.

Developed by a team led by Rice University's Bruce Weisman and Satish Nagarajaiah, the skin is actually a barely-visible very thin film. It consists of a bottom layer of carbon nanotubes dispersed within a polymer, and a top transparent protective layer composed of a different type of polymer (carbon nanotubes are basically microscopic rolled-up sheets of graphene, graphene being a one-atom-thick sheet of linked carbon atoms).

As is the case with carbon nanotubes in general, the ones in the skin fluoresce when subjected to laser light. Depending on how much mechanical strain they're under, however, they'll fluoresce at different wavelengths. Therefore, by analyzing the wavelength of the near-infrared light that the nanotubes are emitting, a handheld reader device can ascertain the amount of strain being exerted on any one area of the skin – and thus on the material underlying it.

The skin has been tested on aluminum bars, which were weakened in one spot with a hole or a notch. While those bars initially appeared uniform to the reader, the skin dramatically indicated where the weakened areas were once the bars were placed under tension.

Going the Way of the Denarius

Going the Way of the Denarius