Breaking News

NYU Prof: Trump's Whole Milk Push Is 'Dog Whistle To Far-Right'

NYU Prof: Trump's Whole Milk Push Is 'Dog Whistle To Far-Right'

Local Police Are Finally Arresting Anti-ICE Agitators In Minnesota

Local Police Are Finally Arresting Anti-ICE Agitators In Minnesota

Watch: Bondi Explodes Over Epstein During Shouting Match With Massie And Top Dems

Watch: Bondi Explodes Over Epstein During Shouting Match With Massie And Top Dems

Top Tech News

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

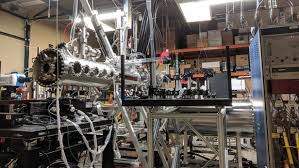

Nuclear fusion breakthrough breathes life into the overlooked Z-pinch approach

Tokamak reactors and fusion stellarators are a couple of the experimental devices used in pursuit of these lofty goals, but scientists at the University of Washington (UW) are taking a far less-frequented route known as a Z-pinch, with the early signs pointing to a cheaper and more efficient path forward.

In order to mimic the conditions inside the Sun, where hydrogen atoms smash together to form helium atoms and release gargantuan amounts of energy with no harmful by-products, we need a whole lot of heat and a whole lot of pressure.

Forming a stream of plasma and holding it in place long enough for these nuclear reactions to occur, either in a twisted loop or a neat donut shape, are the techniques employed by devices like Germany's wonky Wendelstein 7-X fusion reactor and China's Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak. But this approach has its drawbacks, relating to the magnetic coils needed to suspend the ring of plasma, as study author Uri Shumlak explains to New Atlas.

A Defense of 1950s Housewives

A Defense of 1950s Housewives