Breaking News

Quantum walkie-talkie: China tests world's first GPS-free radio for border zones

Quantum walkie-talkie: China tests world's first GPS-free radio for border zones

RIGHT NOW!: Why was lawyer Van Kessel, of the civil case on the merits in the Netherlands, arrested?

RIGHT NOW!: Why was lawyer Van Kessel, of the civil case on the merits in the Netherlands, arrested?

PENSION FUNDS PANIC BUYING SILVER – Ratio Below 60 Triggers $50B Wave (Danger Next Week)

PENSION FUNDS PANIC BUYING SILVER – Ratio Below 60 Triggers $50B Wave (Danger Next Week)

Dollar set for worst year since 2017, yen still in focus

Dollar set for worst year since 2017, yen still in focus

Top Tech News

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

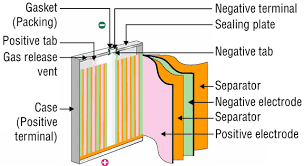

Lithium-ion battery boost could come from "caging" silicon in graphene

The researchers managed to remove two long-standing barriers to these improvements by putting silicon particles in graphene "cages."

To improve capacity in recent years batteries have begun to use silicon anodes, which have more capacity than the graphite conventionally used. But silicon particles also swell so much during charging that they're prone to cracking or shattering and they can also react with the battery electrolyte, forming a coating that reduces performance.

The solution from the team at Stanford and the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is to encase each silicon particle in a "custom-fit cage" of graphene. At only one-atom thick, graphene is the thinnest, strongest form of carbon and also conducts electricity well.

The carbon cages would allow the silicon to expand and even break apart, but keep the pieces together so that they can continue to function. The graphene barrier would also block the destructive chemical reactions with the electrolyte from occurring.