Breaking News

IT'S OVER: Banks Tap Fed for $17 BILLION as Silver Shorts Implode

IT'S OVER: Banks Tap Fed for $17 BILLION as Silver Shorts Implode

SEMI-NEWS/SEMI-SATIRE: December 28, 2025 Edition

China Will Close the Semiconductor Gap After EUV Lithography Breakthrough

China Will Close the Semiconductor Gap After EUV Lithography Breakthrough

The Five Big Lies of Vaccinology

The Five Big Lies of Vaccinology

Top Tech News

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

Process for producing ammonia that generates electricity instead of consuming energy...

Nearly a century ago, German chemist Fritz Haber won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for a process to generate ammonia from hydrogen and nitrogen gases. The process, still in use today, ushered in a revolution in agriculture, but now consumes around one percent of the world's energy to achieve the high pressures and temperatures that drive the chemical reactions to produce ammonia.

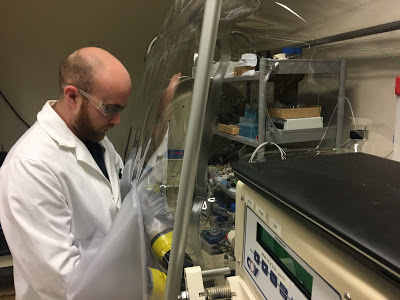

Today, University of Utah chemists publish a different method, using enzymes derived from nature, that generates ammonia at room temperature. As a bonus, the reaction generates a small electrical current.

Although chemistry and materials science and engineering professor Shelley Minteer and postdoctoral scholar Ross Milton have only been able to produce small quantities of ammonia so far, their method could lead to a less energy-intensive source of the ammonia, used worldwide as a vital fertilizer.