Breaking News

Marjorie Taylor Greene EVISCERATES Trump Over Iran War! w/ Rick Overton

Marjorie Taylor Greene EVISCERATES Trump Over Iran War! w/ Rick Overton

Sip your way to better gut health with these science-backed, fermented beverages

Sip your way to better gut health with these science-backed, fermented beverages

The War on Sunlight Is Real (And It's Not an Accident) | Dr. Jack Kruse

The War on Sunlight Is Real (And It's Not an Accident) | Dr. Jack Kruse

Trump's Unconditional Surrender, NEW Supreme Leader Mojtaba Khamenei + NYC IED Attack...

Trump's Unconditional Surrender, NEW Supreme Leader Mojtaba Khamenei + NYC IED Attack...

Top Tech News

The Pentagon is looking for the SpaceX of the ocean.

The Pentagon is looking for the SpaceX of the ocean.

Major milestone by 3D printing an artificial cornea using a specialized "bioink"...

Major milestone by 3D printing an artificial cornea using a specialized "bioink"...

Scientists at Rice University have developed an exciting new two-dimensional carbon material...

Scientists at Rice University have developed an exciting new two-dimensional carbon material...

Footage recorded by hashtag#Meta's AI smart glasses is sent to offshore contractors...

Footage recorded by hashtag#Meta's AI smart glasses is sent to offshore contractors...

ELON MUSK: "With something like Neuralink… we effectively become maybe one with the AI."

ELON MUSK: "With something like Neuralink… we effectively become maybe one with the AI."

DARPA Launches New Program Generative Optogenetics, GO,...

DARPA Launches New Program Generative Optogenetics, GO,...

Anthropic Outpaces OpenAI Revenue 10X, Pentagon vs. Dario, Agents Rent Humans | #234

Anthropic Outpaces OpenAI Revenue 10X, Pentagon vs. Dario, Agents Rent Humans | #234

Ordering a Tiny House from China, what's the real COST?

Ordering a Tiny House from China, what's the real COST?

New video may offer glimpse of secret F-47 fighter

New video may offer glimpse of secret F-47 fighter

Donut Lab's Solid-State Battery Charges Fast. But Experts Still Have Questions

Donut Lab's Solid-State Battery Charges Fast. But Experts Still Have Questions

Science of smell: The first molecular images of odor receptors at work

To help shed some light on the system, researchers at Rockefeller University have taken the first cryo-electron microscope images of an olfactory receptor at work in the simple system of an insect.

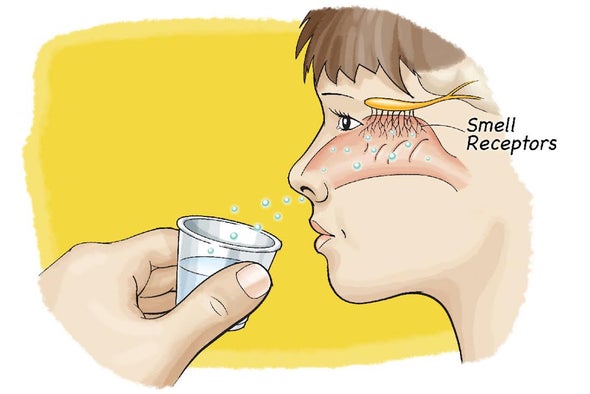

Receptors are key structures that help us understand the world around us through our five senses. There are touch receptors in the skin, photoreceptors in the retina, taste receptors on the tongue, sound-sensitive receptors in the inner ear, and olfactory receptors in the nose. They all respond to different stimuli, opening ion channels to transmit signals to the brain to interpret what we're experiencing.

But the olfactory receptors are the most mysterious of all. While we only need three types in the eyes to see and six in the ear to hear, it takes over 400 receptors to smell – and even these pull double duty to detect the millions of different odorant molecules. A specific smell like coffee or roses is made up of hundreds of chemical components that stimulate different arrangements of receptors, and this precise activation pattern helps the brain decode what exactly it's smelling.

"The olfactory system has to recognize a vast number of molecules with only a few hundred odor receptors or even less," says Vanessa Ruta, corresponding author of the study. "It's clear that it had to evolve a different kind of logic than other sensory systems."

So for the new study, the team set out to study that complex logic. The main question they wanted to answer was how a single receptor is able to recognize different chemicals, despite those molecules having different sizes and shapes.

To find out, they used a technique called cryo-electron microscopy, which involves firing a beam of electrons at a frozen sample to produce a 3D image of its tiny molecular structures. This was performed on the olfactory receptors of an insect called a jumping bristletail, which has a relatively simple odor-sensing system containing only five types of receptors.