Breaking News

Marjorie Taylor Greene EVISCERATES Trump Over Iran War! w/ Rick Overton

Marjorie Taylor Greene EVISCERATES Trump Over Iran War! w/ Rick Overton

Sip your way to better gut health with these science-backed, fermented beverages

Sip your way to better gut health with these science-backed, fermented beverages

The War on Sunlight Is Real (And It's Not an Accident) | Dr. Jack Kruse

The War on Sunlight Is Real (And It's Not an Accident) | Dr. Jack Kruse

Trump's Unconditional Surrender, NEW Supreme Leader Mojtaba Khamenei + NYC IED Attack...

Trump's Unconditional Surrender, NEW Supreme Leader Mojtaba Khamenei + NYC IED Attack...

Top Tech News

The Pentagon is looking for the SpaceX of the ocean.

The Pentagon is looking for the SpaceX of the ocean.

Major milestone by 3D printing an artificial cornea using a specialized "bioink"...

Major milestone by 3D printing an artificial cornea using a specialized "bioink"...

Scientists at Rice University have developed an exciting new two-dimensional carbon material...

Scientists at Rice University have developed an exciting new two-dimensional carbon material...

Footage recorded by hashtag#Meta's AI smart glasses is sent to offshore contractors...

Footage recorded by hashtag#Meta's AI smart glasses is sent to offshore contractors...

ELON MUSK: "With something like Neuralink… we effectively become maybe one with the AI."

ELON MUSK: "With something like Neuralink… we effectively become maybe one with the AI."

DARPA Launches New Program Generative Optogenetics, GO,...

DARPA Launches New Program Generative Optogenetics, GO,...

Anthropic Outpaces OpenAI Revenue 10X, Pentagon vs. Dario, Agents Rent Humans | #234

Anthropic Outpaces OpenAI Revenue 10X, Pentagon vs. Dario, Agents Rent Humans | #234

Ordering a Tiny House from China, what's the real COST?

Ordering a Tiny House from China, what's the real COST?

New video may offer glimpse of secret F-47 fighter

New video may offer glimpse of secret F-47 fighter

Donut Lab's Solid-State Battery Charges Fast. But Experts Still Have Questions

Donut Lab's Solid-State Battery Charges Fast. But Experts Still Have Questions

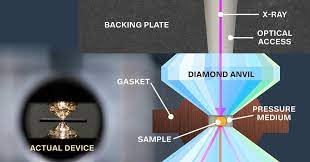

Room-temperature superconductors could zap us into the future

In the future, wires might cross underneath oceans to effortlessly deliver electricity from one continent to another. Those cables would carry currents from giant wind turbines or power the magnets of levitating high-speed trains.

All these technologies rely on a long-sought wonder of the physics world: superconductivity, a heightened physical property that lets metal carry an electric current without losing any juice.

But superconductivity has only functioned at freezing temperatures that are far too cold for most devices. To make it more useful, scientists have to recreate the same conditions at regular temperatures. And even though physicists have known about superconductivity since 1911, a room-temperature superconductor still evades them, like a mirage in the desert.