Breaking News

Will the Next First Turning Be to Technocracy?

Will the Next First Turning Be to Technocracy?

Business Insider: Factcheck Your AI Stories Or Else

Business Insider: Factcheck Your AI Stories Or Else

BREAKING EXCLUSIVE: Judge Delays Tina Peters Justice, Orders Colorado AG to Answer...

"This Individual Needs To Be Investigated!" Alex Jones Responds To Deranged Leftist Destin

"This Individual Needs To Be Investigated!" Alex Jones Responds To Deranged Leftist Destin

Top Tech News

This "Printed" House Is Stronger Than You Think

This "Printed" House Is Stronger Than You Think

Top Developers Increasingly Warn That AI Coding Produces Flaws And Risks

Top Developers Increasingly Warn That AI Coding Produces Flaws And Risks

We finally integrated the tiny brains with computers and AI

We finally integrated the tiny brains with computers and AI

Stylish Prefab Home Can Be 'Dropped' into Flooded Areas or Anywhere Housing is Needed

Stylish Prefab Home Can Be 'Dropped' into Flooded Areas or Anywhere Housing is Needed

Energy Secretary Expects Fusion to Power the World in 8-15 Years

Energy Secretary Expects Fusion to Power the World in 8-15 Years

ORNL tackles control challenges of nuclear rocket engines

ORNL tackles control challenges of nuclear rocket engines

Tesla Megapack Keynote LIVE - TESLA is Making Transformers !!

Tesla Megapack Keynote LIVE - TESLA is Making Transformers !!

Methylene chloride (CH2Cl?) and acetone (C?H?O) create a powerful paint remover...

Methylene chloride (CH2Cl?) and acetone (C?H?O) create a powerful paint remover...

Engineer Builds His Own X-Ray After Hospital Charges Him $69K

Engineer Builds His Own X-Ray After Hospital Charges Him $69K

Researchers create 2D nanomaterials with up to nine metals for extreme conditions

Researchers create 2D nanomaterials with up to nine metals for extreme conditions

'Show Me Your Papers!'

"The right of the people to be secure in their persons,

houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable

searches and seizures shall not be violated,

and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause,

supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing

the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized."

— Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

Last week, in an unsigned order issued without an explanation, and in direct defiance of the plain language of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution, the Supreme Court of the United States permitted federal police to stop persons in public and demand to see proof of lawful presence here — and in the absence of that proof, to arrest them.

Here is the backstory.

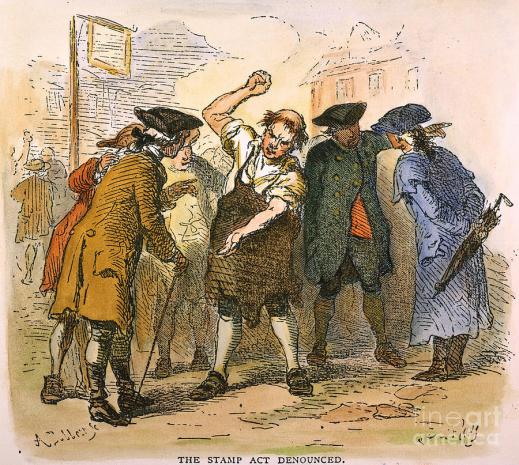

In 1765, when the British king and Parliament were looking for creative ways to tax the colonists in America, Parliament enacted the Stamp Act. This law required the colonists to affix British stamps, purchased from British agents in America, to all papers in one's possession in one's home. The stamps were required on all legal, financial and personal documents; on every book, newspaper and pamphlet; even on broadsides or posters intended to be displayed publicly.

The stated purpose of the Act was to generate revenue to fund British soldiers for security in the colonies. The Act was enforced by the execution of writs of assistance.

In 1765, British agents began to execute these writs of assistance in America. The writs were search warrants that did not describe the place to be searched or the person or things to be seized, but rather authorized the bearer to search wherever he wished and seize whatever he found. These general warrants were issued by a secret court in London upon a showing only of governmental need. Such a showing was, of course, meaningless since whatever the government wanted it would tell the court it needed.

When some students at the College of New Jersey, now known as Princeton University, calculated that the Stamp Act cost more to enforce than was generated in revenue, many colonists realized that this dreadful law was only secondarily a revenue generator. Its true but unstated purpose was to enable the king through his agents to enter colonial homes on the pretext of looking for stamps but truly looking for revolutionary materials.

The colonial reaction was one of such ferocity toward the British sellers of the stamps and the agents who were executing the general warrants that Parliament rescinded the Stamp Act in 1766. But the die had been cast.

After the revolution had been won and the Constitution ratified, the 13 states ratified the first 10 amendments to the Constitution — the Bill of Rights. The theory of the Bill of Rights is not that the new government would grant rights but rather that it was prohibited absolutely by legislation or executive decree from interfering with rights.