Breaking News

Quantum walkie-talkie: China tests world's first GPS-free radio for border zones

Quantum walkie-talkie: China tests world's first GPS-free radio for border zones

RIGHT NOW!: Why was lawyer Van Kessel, of the civil case on the merits in the Netherlands, arrested?

RIGHT NOW!: Why was lawyer Van Kessel, of the civil case on the merits in the Netherlands, arrested?

PENSION FUNDS PANIC BUYING SILVER – Ratio Below 60 Triggers $50B Wave (Danger Next Week)

PENSION FUNDS PANIC BUYING SILVER – Ratio Below 60 Triggers $50B Wave (Danger Next Week)

Dollar set for worst year since 2017, yen still in focus

Dollar set for worst year since 2017, yen still in focus

Top Tech News

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

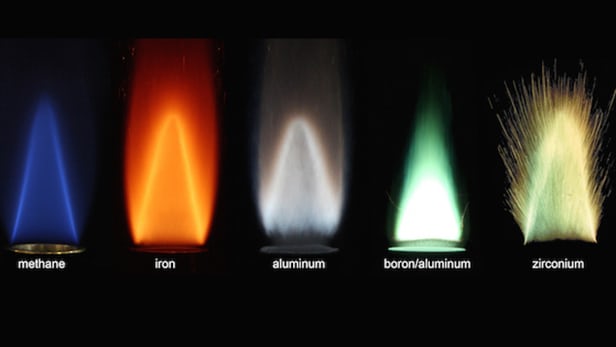

Metal makes for a promising alternative to fossil fuels

The team is studying the combustion characteristics of metal powders to determine whether such powders could provide a cleaner, more viable alternative to fossil fuels than hydrogen, biofuels, or electric batteries.

Metals may seem about as unburnable as it's possible to be, but when ground into extremely fine powder like flour or icing sugar, it's a different story. The simile is an apt one because the metal powders are similar to flour or sugar in more than particle size. Almost anything ground so fine will burn or even explode under the right conditions.

Grinding a powder so fine vastly increases the ratio between the surface area and the volume of the grains, so they burn very readily. In fact, they burn so readily that it's the reason why flour mills are so well ventilated. The slightest spark in floury air and a mill can blow up like a munitions dump. The same goes for sugar, metals, or even some types of rock.

This fact is already employed in a number of areas. Iron or aluminum, for example, can be ground up and turned into colorants for fireworks, solid rocket fuel powerful enough to lift a payload into orbit, or thermite that can burn hot enough to cut steel rails. What the McGill team hopes to do is harness this principle and turn it into a practical power source for everyday use.