Breaking News

AI Data Centers Build Their Own Power Plants Because the Grid Isn't Ready

AI Data Centers Build Their Own Power Plants Because the Grid Isn't Ready

Tucker Responds to the Text Message Scandals and What It Reveals About the Dark Desires of the Left

Tucker Responds to the Text Message Scandals and What It Reveals About the Dark Desires of the Left

AI stock frenzy sparks bubble fears as valuations skyrocket

AI stock frenzy sparks bubble fears as valuations skyrocket

States embrace goldbacks amid dollar decline, offering antifragile currency against centralized...

States embrace goldbacks amid dollar decline, offering antifragile currency against centralized...

Top Tech News

3D Printed Aluminum Alloy Sets Strength Record on Path to Lighter Aircraft Systems

3D Printed Aluminum Alloy Sets Strength Record on Path to Lighter Aircraft Systems

Big Brother just got an upgrade.

Big Brother just got an upgrade.

SEMI-NEWS/SEMI-SATIRE: October 12, 2025 Edition

Stem Cell Breakthrough for People with Parkinson's

Stem Cell Breakthrough for People with Parkinson's

Linux Will Work For You. Time to Dump Windows 10. And Don't Bother with Windows 11

Linux Will Work For You. Time to Dump Windows 10. And Don't Bother with Windows 11

XAI Using $18 Billion to Get 300,000 More Nvidia B200 Chips

XAI Using $18 Billion to Get 300,000 More Nvidia B200 Chips

Immortal Monkeys? Not Quite, But Scientists Just Reversed Aging With 'Super' Stem Cells

Immortal Monkeys? Not Quite, But Scientists Just Reversed Aging With 'Super' Stem Cells

ICE To Buy Tool That Tracks Locations Of Hundreds Of Millions Of Phones Every Day

ICE To Buy Tool That Tracks Locations Of Hundreds Of Millions Of Phones Every Day

Yixiang 16kWh Battery For $1,920!? New Design!

Yixiang 16kWh Battery For $1,920!? New Design!

Find a COMPATIBLE Linux Computer for $200+: Roadmap to Linux. Part 1

Find a COMPATIBLE Linux Computer for $200+: Roadmap to Linux. Part 1

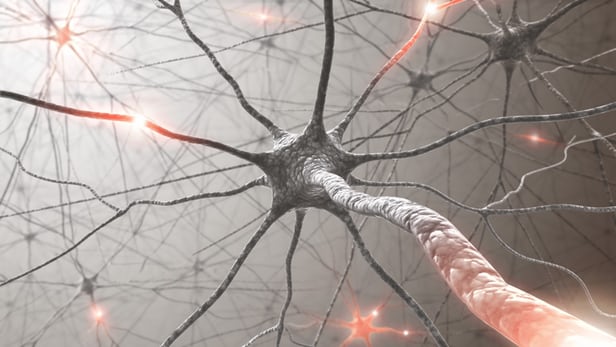

Action of "gatekeeper" cells could be ground zero for Alzheimer's

In the hunt for a cause and cure for Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative ailments, much attention has been focused on sticky proteins called beta-amyloid plaques that build up in the brain and cause nerve damage. A new potential target has been identified by researchers however, in so called "gatekeeper" cells that control the flow of oxygen in the brain.

The cells are known as pericytes and they are found around blood vessels. When they are functioning properly, they control the flow of blood to different parts of the brain by expanding and contracting. When they're not working, or not in plentiful enough supply, they can literally suffocate neurons.

"Pericyte degeneration may be ground zero for neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's disease, ALS and possibly others," said Berislav Zlokovic, senior author of the pericyte study and director of the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California. "A glitch with gatekeeper cells that surround capillaries may restrict blood and oxygen supply to active areas of the brain, gradually causing neuron loss that might have important implications for Alzheimer's disease."

To find out if pericytes should indeed be explored as a possible cause of Alzheimer's disease, the USC researchers bioengineered mice to have 25 percent fewer of them. They then prodded the hind legs of the young specimens with an electric stimulus. The pericyte-lacking mice showed an approximately 30 percent reduction in blood flow in the brain versus normal mice, because their capillaries took about 6.5 seconds longer to open up in the face of the stimulus.

As the mice aged, the cerebral blood-flow response got even worse, dipping to 58 percent lower than their unaffected brethren at six to eight months of age.