Breaking News

The Vain Struggle to Curb Congressional Stock Trading

The Vain Struggle to Curb Congressional Stock Trading

The Tesla Model S Is Dead. Here's Why It Mattered

America's First Car With Solid-State Batteries Could Come From This Little-Known EV Maker

America's First Car With Solid-State Batteries Could Come From This Little-Known EV Maker

POWERFUL EXCLUSIVE: Learn Why Silver, Gold, & Bitcoin Plunged After JD Vance Announced...

POWERFUL EXCLUSIVE: Learn Why Silver, Gold, & Bitcoin Plunged After JD Vance Announced...

Top Tech News

How underwater 3D printing could soon transform maritime construction

How underwater 3D printing could soon transform maritime construction

Smart soldering iron packs a camera to show you what you're doing

Smart soldering iron packs a camera to show you what you're doing

Look, no hands: Flying umbrella follows user through the rain

Look, no hands: Flying umbrella follows user through the rain

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

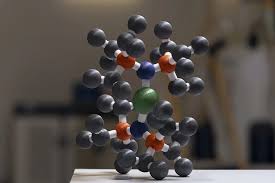

New molecule could create stamp-sized drives with 100x more storage

How much data are we talking here? "This new molecule could lead to new technologies that could store about three terabytes of data per square centimeter," said Professor Nicholas Chilton from the Australian National University (ANU). "That's equivalent to around 40,000 CD copies of The Dark Side of the Moon album squeezed into a hard drive the size of a postage stamp, or around half a million TikTok videos."

To achieve this sort of data density, the team of chemists from ANU and the University of Manchester had to go beyond existing magnetic storage tech. Current drives magnetize small regions of a material to retain memory and that's fine – but the researchers are looking at single-molecule magnets (SMM) which can store data individually to unlock much greater density than ever before.

Imagine a tiny magnet that stores a 1 or 0, similar to computer memory. For these molecular magnets to be useful, they need to reliably hold their magnetic direction (their "memory") across a range of temperatures. Today's single-molecule magnets, especially those made with the metallic element Dysprosium, lose their magnetic memory below about 80 Kelvin (which is -193 °C or -315 °F).

The researchers took it upon themselves to get these magnets to work at higher temperatures than that. They've achieved this by designing and synthesizing a new Dysprosium molecule called 1-Dy. This new molecule maintains its magnetic memory (termed hysteresis) up to 100 Kelvin (-173 °C or -279 °F), which "could be feasible in huge data centers, such as those used by Google," according to co-lead author Professor David Mills.

The new molecule is said to be more stable too, meaning it can withstand a much higher energy barrier to magnetic reversal than previous SMM, and that it would take more energy to flip its magnetic state by accident. The team published its findings in Nature earlier this week.

1-Dy maintains its magnetic memory at higher temperatures than previous magnets because of its unique molecular structure. Since the rare earth element is located between two nitrogen atoms in a straight line, held in place with an alkene bonded to Dysprosium, the molecule's magnetic performance is significantly better than other SMM.