Breaking News

BREAKING: CBS 60 Minutes: revealed a previously unknown weapon that they believe is linked...

BREAKING: CBS 60 Minutes: revealed a previously unknown weapon that they believe is linked...

The Year of Adam Smith: Why the Savvy Scotsman Remains So Important

The Year of Adam Smith: Why the Savvy Scotsman Remains So Important

Trump sons trigger 'corruption' uproar as Pentagon drone venture surfaces amid Iran war

Trump sons trigger 'corruption' uproar as Pentagon drone venture surfaces amid Iran war

Will the Dollar be a Casualty of the Iran War?

Will the Dollar be a Casualty of the Iran War?

Top Tech News

The Pentagon is looking for the SpaceX of the ocean.

The Pentagon is looking for the SpaceX of the ocean.

Major milestone by 3D printing an artificial cornea using a specialized "bioink"...

Major milestone by 3D printing an artificial cornea using a specialized "bioink"...

Scientists at Rice University have developed an exciting new two-dimensional carbon material...

Scientists at Rice University have developed an exciting new two-dimensional carbon material...

Footage recorded by hashtag#Meta's AI smart glasses is sent to offshore contractors...

Footage recorded by hashtag#Meta's AI smart glasses is sent to offshore contractors...

ELON MUSK: "With something like Neuralink… we effectively become maybe one with the AI."

ELON MUSK: "With something like Neuralink… we effectively become maybe one with the AI."

DARPA Launches New Program Generative Optogenetics, GO,...

DARPA Launches New Program Generative Optogenetics, GO,...

Anthropic Outpaces OpenAI Revenue 10X, Pentagon vs. Dario, Agents Rent Humans | #234

Anthropic Outpaces OpenAI Revenue 10X, Pentagon vs. Dario, Agents Rent Humans | #234

Ordering a Tiny House from China, what's the real COST?

Ordering a Tiny House from China, what's the real COST?

New video may offer glimpse of secret F-47 fighter

New video may offer glimpse of secret F-47 fighter

Donut Lab's Solid-State Battery Charges Fast. But Experts Still Have Questions

Donut Lab's Solid-State Battery Charges Fast. But Experts Still Have Questions

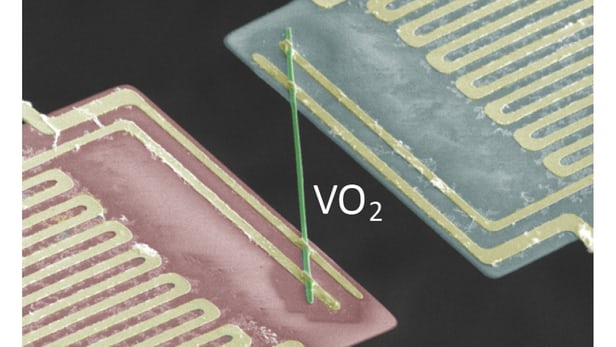

Bizarre metal conducts electricity without heating up

In an apparent contradiction to textbook physics, a metal has been identified that conducts electricity but produces almost no heat in the process. Such a strange property may be expected to occur in conductors operating at cryogenic temperatures, but a team of researchers led by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory claims to have discovered this unique property in vanadium dioxide at temperatures of around 67 °C (153 °F).

Of all the metals found on Earth, most are both good conductors of heat and electricity. This is because classic physics dictates that their electrons are responsible for both the movement of electrical current and the transfer of heat. This correlation between electrical and thermal conductivity is dictated by the Wiedemann-Franz Law, which basically says that metals that conduct electricity well are also good conductors of heat.

However, metallic vanadium dioxide (VO2) seems to be different. When the researchers passed an electrical current through nanoscale rods of single-crystal VO2, and thermal conductivity was measured, the heat produced by electron movement was actually ten times less than that predicted by calculations of the Wiedemann-Franz Law.

"This was a totally unexpected finding," said Professor Junqiao Wu, a physicist at Berkeley Lab's Materials Sciences Division. "It shows a drastic breakdown of a textbook law that has been known to be robust for conventional conductors. This discovery is of fundamental importance for understanding the basic electronic behavior of novel conductors."

And what a novel conductor VO2 is.

When heated to 67 °C (153 °F), vanadium dioxide undergoes an abrupt transition from an insulator to a conductor, as its crystal structure transforms. This structural alignment of VO2 into a metal provides clues as to why the material is able to transfer electrical current with negligible heating.