Breaking News

Iran (So Far Away) - Official Music Video

Iran (So Far Away) - Official Music Video

COMEX Silver: 21 Days Until 429 Million Ounces of Demand Meets 103 Million Supply. (March Crisis)

COMEX Silver: 21 Days Until 429 Million Ounces of Demand Meets 103 Million Supply. (March Crisis)

Marjorie Taylor Greene: MAGA Was "All a Lie," "Isn't Really About America or the

Marjorie Taylor Greene: MAGA Was "All a Lie," "Isn't Really About America or the

Why America's Two-Party System Will Never Threaten the True Political Elites

Why America's Two-Party System Will Never Threaten the True Political Elites

Top Tech News

How underwater 3D printing could soon transform maritime construction

How underwater 3D printing could soon transform maritime construction

Smart soldering iron packs a camera to show you what you're doing

Smart soldering iron packs a camera to show you what you're doing

Look, no hands: Flying umbrella follows user through the rain

Look, no hands: Flying umbrella follows user through the rain

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

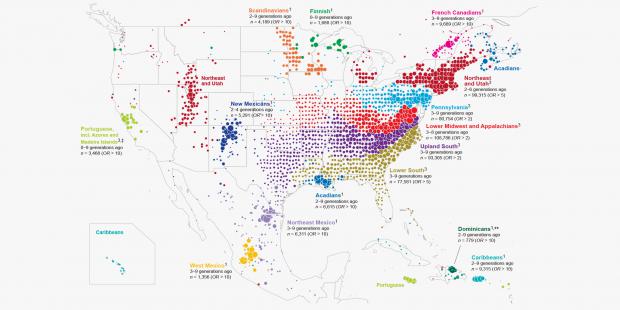

770,000 Tubes of Spit Help Map America's Great Migrations

Using more than 770,000 spit samples taken from their customers over the last five years, its researchers mapped how people moved and married in post-colonial America. And their choices—especially the ones that kept communities apart—shaped today's modern genetic landscape.

The study, published today in Nature Communications, combines a DNA database with family tree information collected over the company's 34-year history. "We're all living under the assumption that we are individual agents," says Catherine Ball, chief scientific officer at Ancestry and the leader of the study. "But people actually are living in the course of history." And from the moment they spit, send, and consent, DNA kit customers become actors in a much larger story—told through the massive data sets companies like Ancestry are accumulating from casual genealogists.

Ball's team of geneticists and statisticians started by pulling out subsets of closely related people from their 770,000 spit samples. In that analysis, each person appears as a dot, while their genetic relationships to everyone else in the database are sticks. The result, Ball says, "looks like a giant hairball."

From that hairball her team pulled out more than 60 unique genetic communities—Germans in Iowa and Mennonites in Kansas and Irish Catholics on the Eastern seaboard. Then they mined their way through generations of family trees (also provided by their customers) to build a migratory map. Finally, they paired up with a Harvard historian to understand why communities moved and dispersed the ways they did. Religion and race were powerful deterrents to gene flow. But nothing, it turned out, was stronger than the Mason Dixon line.