Breaking News

Quantum walkie-talkie: China tests world's first GPS-free radio for border zones

Quantum walkie-talkie: China tests world's first GPS-free radio for border zones

RIGHT NOW!: Why was lawyer Van Kessel, of the civil case on the merits in the Netherlands, arrested?

RIGHT NOW!: Why was lawyer Van Kessel, of the civil case on the merits in the Netherlands, arrested?

PENSION FUNDS PANIC BUYING SILVER – Ratio Below 60 Triggers $50B Wave (Danger Next Week)

PENSION FUNDS PANIC BUYING SILVER – Ratio Below 60 Triggers $50B Wave (Danger Next Week)

Dollar set for worst year since 2017, yen still in focus

Dollar set for worst year since 2017, yen still in focus

Top Tech News

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

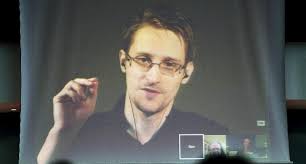

Edward Snowden's New Job: Protecting Reporters From Spies

When Edward Snowden leaked the biggest collection of classified National Security Agency documents in history, he wasn't just revealing the inner workings of a global surveillance machine. He was also scrambling to evade it. To communicate with the journalists who would publish his secrets, he had to route all his messages over the anonymity software Tor, teach reporters to use the encryption tool PGP by creating a YouTube tutorial that disguised his voice, and eventually ditch his comfortable life (and smartphone) in Hawaii to set up a cloak-and-dagger data handoff halfway around the world.

Now, nearly four years later, Snowden has focused the next phase of his career on solving that very specific instance of the panopticon problem: how to protect reporters and the people who feed them information in an era of eroding privacy—without requiring them to have an NSA analyst's expertise in encryption or to exile themselves to Moscow. "Watch the journalists and you'll find their sources," Snowden says. "So how do we preserve that confidentiality in this new world, when it's more important than ever?"

Since early last year, Snowden has quietly served as president of a small San Francisco–based nonprofit called the Freedom of the Press Foundation. Its mission: to equip the media to do its job at a time when state-sponsored hackers and government surveillance threaten investigative reporting in ways Woodward and Bernstein never imagined. "Newsrooms don't have the budget, the sophistication, or the skills to defend themselves in the current environment," says Snowden, who spoke to WIRED via encrypted video-chat from his home in Moscow. "We're trying to provide a few niche tools to make the game a little more fair."

The group's 10 staffers and a handful of contract coders, with Snowden's remote guidance, are working to develop an armory of security upgrades for reporters. Snowden and renowned hacker Bunnie Huang have partnered to develop a hardware modification for the iPhone, designed to detect if malware on the device is secretly transmitting a reporter's data, including location. They've recruited Fred Jacobs, one of the coders for the popular encryption app Signal, to help build a piece of software called Sunder; the tool would allow journalists to encrypt a trove of secrets and then retrieve them only if several newsroom colleagues combine their passwords to access the data.