Breaking News

Bill Maher APOLOGIZES To QAnon!

Bill Maher APOLOGIZES To QAnon!

Mama's Boy? Sam Bankman-Fried, Represented By His Mother, Files For New Trial In FTX Implosion C

Mama's Boy? Sam Bankman-Fried, Represented By His Mother, Files For New Trial In FTX Implosion C

China Is Collapsing - The Truth Behind America's Greatest Rival!

China Is Collapsing - The Truth Behind America's Greatest Rival!

I Tried Extreme Celebrity Biohacks (Here's What Actually Works)

I Tried Extreme Celebrity Biohacks (Here's What Actually Works)

Top Tech News

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

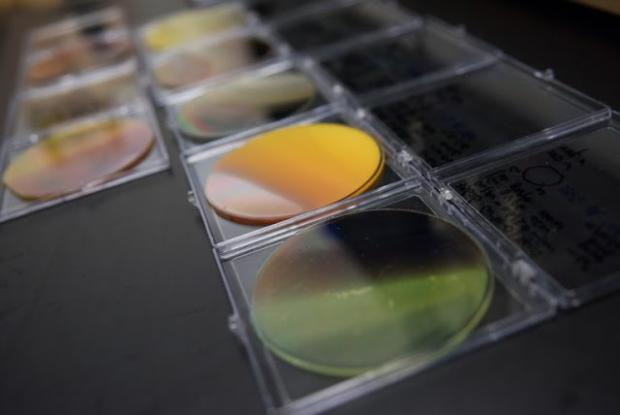

New Materials Could Turn Water into the Fuel of the Future and puts chemical ...

Scientists at the Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have—in just two years—nearly doubled the number of materials known to have potential for use in solar fuels.

They did so by developing a process that promises to speed the discovery of commercially viable generation of solar fuels that could replace coal, oil, and other fossil fuels.

Solar fuels, a dream of clean-energy research, are created using only sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide. Researchers are exploring a range of possible target fuels, but one possibility is to produce hydrogen by splitting water.

Each water molecule is comprised of an oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms. Pure hydrogen is highly flammable, making it an ideal fuel. If you could find a way to extract that hydrogen from water using sunlight, then, you would have a plentiful and renewable energy source. The problem, however, is that water molecules do not simply break down when sunlight shines on them—if they did, the oceans would not cover three-fourths of the planet. Instead, they need a little help from a solar-powered catalyst.

To create practical solar fuels, scientists have been trying to develop low-cost and efficient materials that perform the necessary chemistry using only visible light as an energy source.

Over the past four decades, researchers identified only 16 of these "photoanode" materials. Now, using a new high-throughput method of identifying new materials, a team of researchers led by Caltech's John Gregoire and Berkeley Lab's Jeffrey Neaton, Kristin Persson, and Qimin Yan have found 12 promising new photoanodes.