Breaking News

If You Grew Up In The 1970s, You Probably Possess These Rare Traits

If You Grew Up In The 1970s, You Probably Possess These Rare Traits

EVEN More SUPER SHADY Financial Dealings At TPUSA!

EVEN More SUPER SHADY Financial Dealings At TPUSA!

British woman warns American about the Rise of Islam...

British woman warns American about the Rise of Islam...

Saks Global prepares for bankruptcy after missing debt payment, WSJ reports

Saks Global prepares for bankruptcy after missing debt payment, WSJ reports

Top Tech News

Laser weapons go mobile on US Army small vehicles

Laser weapons go mobile on US Army small vehicles

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

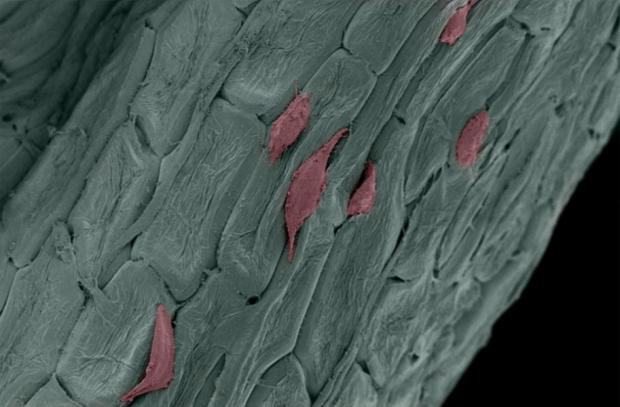

Parsley and vanilla beans are being used as cellular scaffolding to grow stem cell tissues

Researchers at the University of Washington-Madison were able to grow skin, brain, bone marrow and blood vessels on plants using a highly-specialized, natural scaffolding from plants like parsley. The team observed that certain plant species possess strength, rigidity and porosity as well as low mass and surface area. These characteristics make for a structurally-efficient scaffold. Plants have really high surface area to volume ratio, while their porous structure facilitates fluid transport, a study author said. The researchers also found that the 3D printed stem cell scaffold helped support, feed and organize the cells.

The researchers have collaborated with the Olbrich Botanical Gardens to identify plant species that show scaffolding potential, which in turn could be turned into structures for biomedical purposes. John Wirth, Olbrich's conservatory curator, said the idea was a good way to use the living plant material to develop human tissue. Parsley, orchid, and vanilla were among the plant species chosen for the study. Bamboo, wasabi, and elephant ear plant were also among the plants were cellulose was derived. "Nature provides us with a tremendous reservoir of structures in plants. You can pick the structure you want," said Gianluca Fontana, the lead author of the new study and a UW-Madison postdoctoral fellow.

"Plants have a huge capacity to grow cell populations. They can deliver fluids very efficiently to their leaves … At the microscale, they're very well organized," said Bill Murphy, co-director of the UW-Madison Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine Center.

"The vast diversity in the plant kingdom provides virtually any size and shape of interest. It really seemed obvious. Plants are extraordinarily good at cultivating new tissues and organs, and there are thousands of different plant species readily available. They represent a tremendous feedstock of new materials for tissue engineering applications," Murphy added.

Study details: Cellulose and 3D scaffolding techniques

The researchers decellularized the plant materials leaving only cellulose, the basic components of a plant's cell walls. The team then added peptides to serve as biological fasteners since human cells have no affinity to cellulose. Advanced technologies such as 3D printing and injection molding were used to create the three-dimensional scaffolds.

It was found that eliminating all the other cells that make up the plant and retaining only the cellulose husks encouraged human stem cells such as fibroblasts to attach to the scaffold and develop miniature structures. Fibroblasts are common connective tissue cells that result from stem cell cultivation.

Stem cells seeded into the scaffold also appeared to align themselves along its structure. This mechanism indicates a potential to use the materials in order to regulate the structure and alignment of developing human tissues, which may prove crucial for nerve and muscle tissues that need alignment and patterning. "Stem cells are sensitive to topography. It influences how cells grow and how well they grow," lead author Gianluca Fontana said.