Breaking News

6.5x55 Swedish vs. 6.5 Creedmoor: The New 6.5mm Hotness

Best 7mm PRC Ammo: Hunting and Long-Distance Target Shooting

Christmas Truce of 1914, World War I - For Sharing, For Peace

Christmas Truce of 1914, World War I - For Sharing, For Peace

Top Tech News

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

Electron magnetic moments may achieve 100 times more computer memory storage

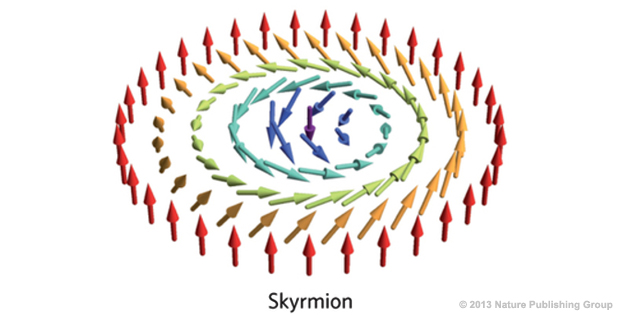

Many people who use computers and other digital devices are aware that all the words and images displayed on their monitors boil down to a sequence of ones and zeros. But few likely appreciate what is behind those ones and zeros: microscopic arrays of "magnetic moments" (imagine tiny bar magnets with positive and negative poles). When aligned in parallel in ferromagnetic materials such as iron, these moments create patterns and streams of magnetic bits—the ones and zeros that are the lifeblood of all things digital.

These magnetic bits are stable against perturbations, such as from heat, by a form of strength in numbers: any moment that inadvertently has its orientation reversed is flipped back by the magnetic interaction with the rest of the aligned moments in the bit. For decades, engineers have been able to increase computing capabilities by shrinking these magnetic domains using advances in manufacturing and novel techniques for reading and writing the data.

In recent years, however, it has become clear that this approach cannot go on indefinitely. As it turns out, moments start to wobble out of alignment when the size of the bit gets too small and the interaction energy keeping them aligned is exceeded by the surrounding thermal energy making the all-important digital bits unstable and unreliable for storage or logic. For a number of high-performance electronic devices, that thermodynamic requirement for magnetic bit size—called the superparamagnetic limit—is about to be reached, meaning that eking out more memory in the same amount of space will no longer be possible.

DARPA's Topological Excitations in Electronics program, announced today, aims to investigate new ways to arrange these moments in novel geometries that are much more stable than the conventional parallel arrangement. If successful, these new configurations could enable bits of data to be made radically smaller than possible today, potentially yielding a 100-fold increase in the amount of storage achievable on a chip. It could also enable designs for completely new computer logic concepts and even for topologically protected "quantum" bits—the basis for long-sought quantum computers.

"We've known for some time that there are some magnetic interactions that favor the magnetic moments being canted in a v-shape rather than the parallel arrangement, which yield a much more stable structure than having them all in parallel," said Rosa Alejandra "Ale" Lukaszew, a program manager in DARPA's Defense Sciences Office. "The canted interaction doesn't allow the electrons to line up parallel to each other, so in order to fit them in a small region they must be configured in a special pattern. These unique geometric patterns, called topological excitations, are very stable and maintain their geometry even when shrunk to very small sizes. But only recently have we had the multiscale models, advanced metrology tools, and understanding of proper material combinations to fully explore this phenomenon."

Another unique characteristic about topological excitations is that they can be moved at significant speed with a small amount of current, allowing for fast read and write operations if, for example, they are placed on a track that runs in front of a read/write head, Ale said. Such an approach would make it possible to explore novel, 3-D approaches to chip design, enabling storage capabilities of 100 Terabits per square inch, 100 times more than the current limit of 1 Terabit per square inch in laboratory demos.

A key goal of the program is to demonstrate topological excitations smaller than 10 nanometers at room temperature for memory applications. Currently there is preliminary research data showing that it is possible to create skyrmions (a particular type of topological excitation) of this size but only at very low temperatures, Ale said. The smallest sizes achieved to date at room temperature are 10s of nanometers, one to two orders of magnitude larger than the new program's goal. However, sizes less than 10 nm are theoretically possible if the right materials can be found.

The State's Last Stand

The State's Last Stand