Breaking News

COMEX Silver: 21 Days Until 429 Million Ounces of Demand Meets 103 Million Supply. (March Crisis)

COMEX Silver: 21 Days Until 429 Million Ounces of Demand Meets 103 Million Supply. (March Crisis)

Marjorie Taylor Greene: MAGA Was "All a Lie," "Isn't Really About America or the

Marjorie Taylor Greene: MAGA Was "All a Lie," "Isn't Really About America or the

Why America's Two-Party System Will Never Threaten the True Political Elites

Why America's Two-Party System Will Never Threaten the True Political Elites

Generation Now #7 – Youth in Davos | Youth Pulse 2026 | Skills That Matter

Generation Now #7 – Youth in Davos | Youth Pulse 2026 | Skills That Matter

Top Tech News

How underwater 3D printing could soon transform maritime construction

How underwater 3D printing could soon transform maritime construction

Smart soldering iron packs a camera to show you what you're doing

Smart soldering iron packs a camera to show you what you're doing

Look, no hands: Flying umbrella follows user through the rain

Look, no hands: Flying umbrella follows user through the rain

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

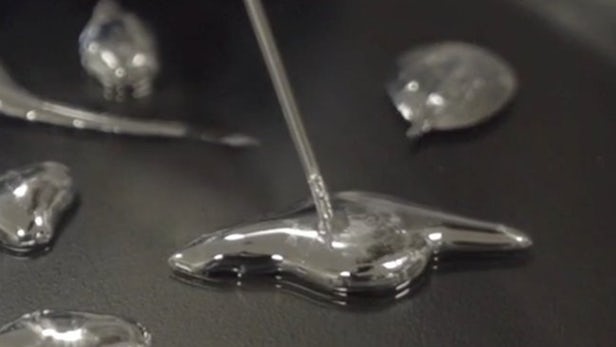

Transistor breakthrough brings liquid computers closer to reality

In a step towards creating a new class of electronics that look and feel like soft, natural organisms, mechanical engineers at Carnegie Mellon University are developing a fluidic transistor out of a metal alloy of indium and gallium that is liquid at room temperature. From biocompatible disease monitors to shape-shifting robots, the potential applications for such squishy computers are intriguing.

Until recently, the only example of liquid electronics were microswitches made up of tiny glass tubes with a bead of mercury inside that closes the switch when it rolls between two wires. Essentially, the fluidic transistor is a much more sophisticated switch that's made of a liquid metal alloy that is non-toxic, so it can be infused into rubber to create soft, stretchable circuits.

Unlike the mercury switch, where tilting the vial closes the circuit, the fluidic transistor works by opening and closing the connection between metal droplets using the direction of the voltage. When it flows in one direction, the droplets combine and the circuit closes. If it flows the other way, the droplet splits and the circuit opens.

Researchers Carmel Majidi and James Wissman of the Soft Machines Lab at Carnegie Mellon say that alternating the opening and closing of the switch allows it to mimic a transistor, thanks to the phenomenon of capillary instability. The hard part was getting inducing the instability so the droplets change from two to one and back seamlessly.

"We see capillary instabilities all the time," says Majidi. "If you turn on a faucet and the flow rate is really low, sometimes you'll see this transition from a steady stream to individual droplets. That's called a Rayleigh instability."

By testing the droplets in a sodium hydroxide bath the engineers found that there was a relationship between the voltage and an electrochemical reaction where voltage produced a gradient in the oxidation on the droplet's surface, altering the surface tension and causing the droplet to split in two. More important, the properties of the switch acted like a transistor.