Breaking News

Christmas Truce of 1914, World War I - For Sharing, For Peace

Christmas Truce of 1914, World War I - For Sharing, For Peace

The Roots of Collectivist Thinking

The Roots of Collectivist Thinking

What Would Happen if a Major Bank Collapsed Tomorrow?

What Would Happen if a Major Bank Collapsed Tomorrow?

Top Tech News

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

A microbial cleanup for glyphosate just earned a patent. Here's why that matters

A microbial cleanup for glyphosate just earned a patent. Here's why that matters

Japan Breaks Internet Speed Record with 5 Million Times Faster Data Transfer

Japan Breaks Internet Speed Record with 5 Million Times Faster Data Transfer

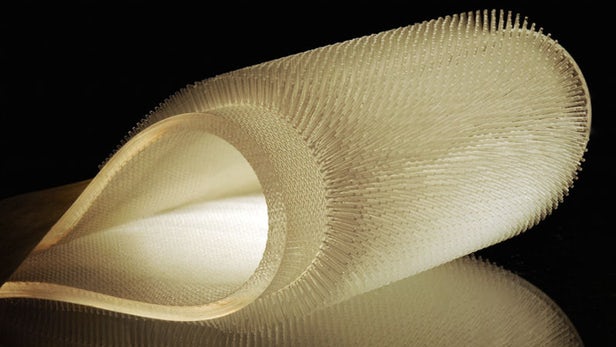

For warmer surfers, leave it to beaver-inspired wetsuits

Even though they don't have a thick layer of blubber, animals such as beavers and sea otters are still able to stay warm when diving in frigid waters. How do they do it? Well, they trap an insulating layer of air between the hairs of their fur. MIT scientists have taken that concept and run with it (or swum with it), creating a bioinspired material that could be used to make lighter, warmer wetsuits.

Last year, lead scientist Prof. Anette (Peko) Hosoi and a group of students visited the Taiwan headquarters of sporting goods manufacturer Sheico Group. The company was interested in creating wetsuits that were better able to let surfers quickly shed water when getting up on their boards, yet still remain warm when submerged.

The researchers already knew about small semiaquatic mammals' ability to trap air in their fur, and set about looking for ways to replicate that quality using manmade materials. In order to do so, they created a number of "fur-like surfaces" molded from a soft rubber called PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane).

These samples, which featured differing densities and lengths of individual rubber hairs, were then mounted on a vertical motorized stage (fur-side facing out) and dunked in silicone oil at varying speeds. By observing close-up video of the dunkings, the scientists were able to determine which samples were best at trapping air, and at what dive speeds.

Based on those observations, they developed a mathematical model that could be applied to the manufacture of wetsuits.

"People have known that these animals use their fur to trap air," says Hosoi. "But, given a piece of fur, they couldn't have answered the question: Is this going to trap air or not? We have now quantified the design space and can say, 'If you have this kind of hair density and length and are diving at these speeds, these designs will trap air, and these will not'."

The State's Last Stand

The State's Last Stand