Breaking News

Bret Weinstein's Thoughts on Charlie Kirk and Iran

Bret Weinstein's Thoughts on Charlie Kirk and Iran

We Are the Villains in This Story

We Are the Villains in This Story

My Prediction For the War with Iran

My Prediction For the War with Iran

Foreign Hacker Cracked Into FBI's Epstein Files In 2023, Was 'Disgusted' At Child Sexual

Foreign Hacker Cracked Into FBI's Epstein Files In 2023, Was 'Disgusted' At Child Sexual

Top Tech News

Human Brain Cells Merge With Silica To Play DOOM

Human Brain Cells Merge With Silica To Play DOOM

Will Yann LeCun Provide The Next Breakthrough In AI?

Will Yann LeCun Provide The Next Breakthrough In AI?

Human Brain Cells Merge With Silica To Play DOOM

Human Brain Cells Merge With Silica To Play DOOM

Solar And Storage Could Reshape Rural Electricity Markets

Solar And Storage Could Reshape Rural Electricity Markets

With World Seemingly At War, DARPA Finds Time To Unveil The X-76

With World Seemingly At War, DARPA Finds Time To Unveil The X-76

The world's first diesel plug-in hybrid pickup truck is here

The world's first diesel plug-in hybrid pickup truck is here

US advances nuclear revival with approval of Natrium Gen IV reactor

US advances nuclear revival with approval of Natrium Gen IV reactor

Your Contractor Doesn't Want Me To Show You This!

Your Contractor Doesn't Want Me To Show You This!

CEO of Blacklisted AI Company Anthropic, Dario Amodei Says His AI Models 'May Have Gained...

CEO of Blacklisted AI Company Anthropic, Dario Amodei Says His AI Models 'May Have Gained...

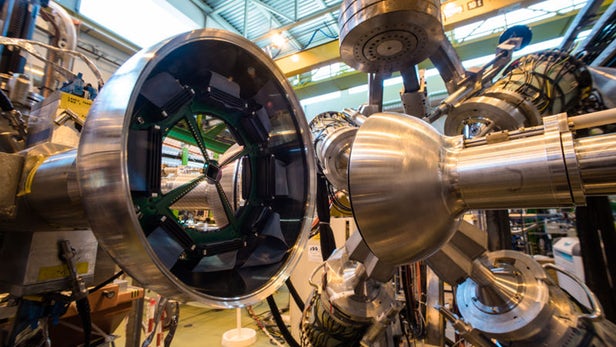

CERN scientists get antimatter ready for its first road trip

Antimatter is notoriously tricky to store and study, thanks to the fact that it will vanish in a burst of energy if it so much as touches regular matter. The CERN lab is one of the only places in the world that can readily produce the stuff, but getting it into the hands of the scientists who want to study it is another matter (pun not intended). After all, how can you transport something that will annihilate any physical container you place it in? Now, CERN researchers are planning to trap and truck antimatter from one facility to another.

Antimatter is basically the evil twin of normal matter. Each antimatter particle is identical to its ordinary counterpart in almost every way, except it carries the opposite charge, leading the two to destroy each other if they come into contact. Neutron stars and jets of plasma from black holes may be natural sources, and it even seems to be formed in the Earth's atmosphere with every bolt of lightning.

Studying antimatter could help us unlock some of the Universe's most profound mysteries – but, of course, the Universe isn't giving up those answers easily. Positrons (or anti-electrons) were the first antimatter particles to be observed in experiments in the 1930s, and like regular matter, these antiparticles clump together to form atoms of antimatter.

Antihydrogen atoms were first created at CERN in 1995, but it wasn't until 2010 that scientists managed to trap and study them properly – even if only for fractions of a second. In 2011, researchers managed to hold onto the antimatter atoms for a solid 16 minutes, allowing them to eventually study their spectra to see how they compare to regular old hydrogen.

Nowadays, CERN can readily produce antiprotons in a particle decelerator, slowing them down to be captured in a specially-designed trap. But to really make the most of them, it's time for the volatile substance to leave the nest, and be put to work in other areas of research.

Renewable Water From Air.

Renewable Water From Air.