Breaking News

Losing Chickens? Tools Needed for Trapping Poultry Predators

Losing Chickens? Tools Needed for Trapping Poultry Predators

Metals Tell the Truth About the Economy

Metals Tell the Truth About the Economy

RFK Jr. baffled over how Trump is alive with diet 'full of poison,'

RFK Jr. baffled over how Trump is alive with diet 'full of poison,'

Dr. Peter McCullough Responds To Anthony Fauci Criminal Referral

Dr. Peter McCullough Responds To Anthony Fauci Criminal Referral

Top Tech News

Superheat Unveils the H1: A Revolutionary Bitcoin-Mining Water Heater at CES 2026

Superheat Unveils the H1: A Revolutionary Bitcoin-Mining Water Heater at CES 2026

World's most powerful hypergravity machine is 1,900X stronger than Earth

World's most powerful hypergravity machine is 1,900X stronger than Earth

New battery idea gets lots of power out of unusual sulfur chemistry

New battery idea gets lots of power out of unusual sulfur chemistry

Anti-Aging Drug Regrows Knee Cartilage in Major Breakthrough That Could End Knee Replacements

Anti-Aging Drug Regrows Knee Cartilage in Major Breakthrough That Could End Knee Replacements

Scientists say recent advances in Quantum Entanglement...

Scientists say recent advances in Quantum Entanglement...

Solid-State Batteries Are In 'Trailblazer' Mode. What's Holding Them Up?

Solid-State Batteries Are In 'Trailblazer' Mode. What's Holding Them Up?

US Farmers Began Using Chemical Fertilizer After WW2. Comfrey Is a Natural Super Fertilizer

US Farmers Began Using Chemical Fertilizer After WW2. Comfrey Is a Natural Super Fertilizer

Kawasaki's four-legged robot-horse vehicle is going into production

Kawasaki's four-legged robot-horse vehicle is going into production

The First Production All-Solid-State Battery Is Here, And It Promises 5-Minute Charging

The First Production All-Solid-State Battery Is Here, And It Promises 5-Minute Charging

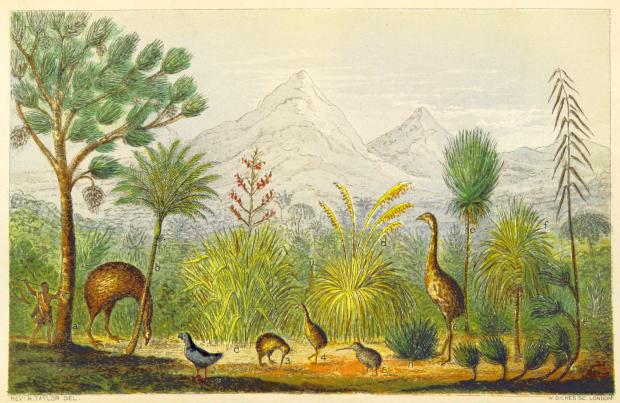

With DNA from a museum specimen, scientists reconstruct the genome of a bird extinct...

Scientists at Harvard University have assembled the first nearly complete genome of the little bush moa, a flightless bird that went extinct soon after Polynesians settled New Zealand in the late 13th century. The achievement moves the field of extinct genomes closer to the goal of "de-extinction" — bringing vanished species back to life by slipping the genome into the egg of a living species, "Jurassic Park"-like.

"De-extinction probability increases with every improvement in ancient DNA analysis," said Stewart Brand, co-founder of the nonprofit conservation group Revive and Restore, which aims to resurrect vanished species including the passenger pigeon and the woolly mammoth, whose genomes have already been mostly pieced together.

For the moa, whose DNA was reconstructed from the toe bone of a museum specimen, that might require a little more genetic tinkering and a lot of egg: The 6-inch long, 1-pounder that emus lay might be just the ticket.

Storage doesn't get much cheaper than this

Storage doesn't get much cheaper than this