Breaking News

BREAKING: Assault Weapons Ban Just Passed For 2026 : 10 Years Prison Who Own This!

BREAKING: Assault Weapons Ban Just Passed For 2026 : 10 Years Prison Who Own This!

Zelensky To Trump: 'Give Me 50 Year Security Guarantee...And More Money!'

Zelensky To Trump: 'Give Me 50 Year Security Guarantee...And More Money!'

I've Never Seen A USB-C Charger This Good!

I've Never Seen A USB-C Charger This Good!

China Just Broke The Silver Market

China Just Broke The Silver Market

Top Tech News

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

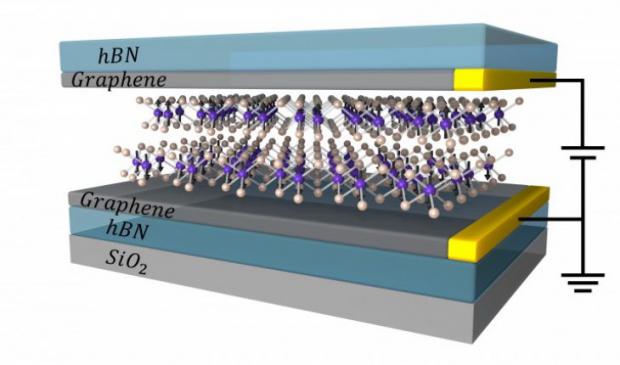

Atom thin magnetic memory

Researchers report that they used stacks of ultrathin materials to exert unprecedented control over the flow of electrons based on the direction of their spins — where the electron "spins" are analogous to tiny, subatomic magnets. The materials that they used include sheets of chromium tri-iodide (CrI3), a material described in 2017 as the first ever 2-D magnetic insulator. Four sheets — each only atoms thick — created the thinnest system yet that can block electrons based on their spins while exerting more than 10 times stronger control than other methods.

"Our work reveals the possibility to push information storage based on magnetic technologies to the atomically thin limit," said co-lead author Tiancheng Song, a UW doctoral student in physics.

Science – Giant tunneling magnetoresistance in spin-filter van der Waals heterostructures

With up to four layers of CrI3, the team discovered the potential for "multi-bit" information storage. In two layers of CrI3, the spins between each layer are either aligned in the same direction or opposite directions, leading to two different rates that the electrons can flow through the magnetic gate. But with three and four layers, there are more combinations for spins between each layer, leading to multiple, distinct rates at which the electrons can flow through the magnetic material from one graphene sheet to the other.

"Instead of your computer having just two choices to store a piece of data in, it can have a choice A, B, C, even D and beyond," said co-author Bevin Huang, a UW doctoral student in physics. "So not only would storage devices using CrI3 junctions be more efficient, but they would intrinsically store more data."