Breaking News

Why are young women attracted to older men? Men, watch and learn!

Why are young women attracted to older men? Men, watch and learn!

Voter Fraud Is About To Explode: ITS BLOWING UP IN THEIR FACES thanks to Trump and Tulsi

Voter Fraud Is About To Explode: ITS BLOWING UP IN THEIR FACES thanks to Trump and Tulsi

Ahead of US-Iran Talks, Netanyahu Tells Cabinet 'Conditions' Could Lead to Regime Change...

Ahead of US-Iran Talks, Netanyahu Tells Cabinet 'Conditions' Could Lead to Regime Change...

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Top Tech News

How underwater 3D printing could soon transform maritime construction

How underwater 3D printing could soon transform maritime construction

Smart soldering iron packs a camera to show you what you're doing

Smart soldering iron packs a camera to show you what you're doing

Look, no hands: Flying umbrella follows user through the rain

Look, no hands: Flying umbrella follows user through the rain

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

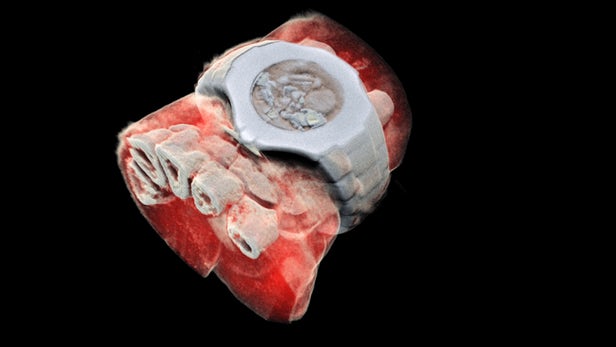

CERN chip enables first 3D color X-ray images of the human body

Medical X-ray scans have long been stuck in the black-and-white, silent-movie era. Sure, the contrast helps doctors spot breaks and fractures in bones, but more detail could help pinpoint other problems. Now, a company from New Zealand has developed a bioimaging scanner that can produce full color, three dimensional images of bones, lipids, and soft tissue, thanks to a sensor chip developed at CERN for use in the Large Hadron Collider.

Mars Bioimaging, the company behind the new scanner, describes the leap as similar to that of black-and-white to color photography. In traditional CT scans, X-rays are beamed through tissue and their intensity is measured on the other side. Since denser materials like bone attenuate (weaken the energy) of X-rays more than soft tissue does, their shape becomes clear as a flat, monochrome image.

But for the new technology, which Mars calls "Spectral CT," the sensor can measure the attenuation of specific wavelengths of the X-rays as they pass through different materials. After running the spectroscopic data through specific algorithms, a 3D color image is generated that clearly shows muscle, bone, water, fat, disease markers – and even a watch. The end results are unnerving, like someone's sculpted a detailed clay model of your insides.

At the heart of the Spectral CT scanner is a Medipix3 chip. This device, which detects and counts every individual particle that hits each pixel on the sensor, was originally developed at CERN to precisely track particles in the Large Hadron Collider.

A small version of the device has been tested to see how well it can diagnose bone and joint health, spot cancer, and pick up early markers for vascular diseases. So far, the results have been promising, the team says.

"In all of these studies, promising early results suggest that when spectral imaging is routinely used in clinics it will enable more accurate diagnosis and personalization of treatment," says Anthony Butler, one of the creators of the 3D scanner.