Breaking News

Importing Poverty into America: Devolving Our Nation into Stupid

Grand Theft World Podcast 273 | Goys 'R U.S. with Guest Rob Dew

Grand Theft World Podcast 273 | Goys 'R U.S. with Guest Rob Dew

Anchorage was the Receipt: Europe is Paying the Price… and Knows it.

Anchorage was the Receipt: Europe is Paying the Price… and Knows it.

The Slow Epstein Earthquake: The Rupture Between the People and the Elites

The Slow Epstein Earthquake: The Rupture Between the People and the Elites

Top Tech News

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

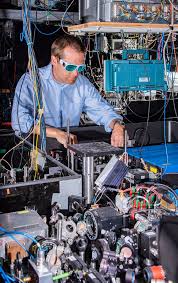

Record-breaking atomic clocks precise enough to measure spacetime distortions

In recent tests run by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), experimental atomic clocks have achieved record performance in three metrics, meaning these clocks could help measure the Earth's gravity more precisely or detect elusive dark matter.

The NIST clocks are made up of 1,000 ytterbium atoms, suspended in a grid of laser beams. These lasers "tick" trillions of times per second, which in turn cause the atoms to consistently flicker between two energy levels like a metronome. Measuring these allows atomic clocks to keep time incredibly precisely, in some cases losing only a single second over 300 million years.

But there's always room for improvement, in this case by adding thermal and electric shielding to the devices. By comparing two experimental atomic clocks, NIST scientists have now reported three new records in the devices at once: systematic uncertainty, stability and reproducibility.

Systematic uncertainty refers to how accurately the clock's ticks match the natural vibrations of the atoms inside it. According to the team, the atomic clocks were correct to within 1.4 errors in a quintillion (a 10 followed by 18 zeroes).

Stability is a measure of how much the clock's ticks change over time. In this case, the NIST clocks were stable to within 3.2 parts in 1019 (a 10 with 19 zeroes) over the course of a day.

And, finally, reproducibility is measured by comparing how well two atomic clocks remain in sync. Checking the two clocks 10 times, the team found that the difference in frequency of their ticking was within a quintillionth.