Breaking News

Zone 00: Permaculture for the Inner Landscape (No Land Required)

Zone 00: Permaculture for the Inner Landscape (No Land Required)

Sam Bankman-Fried files for new trial over FTX fraud charges

Sam Bankman-Fried files for new trial over FTX fraud charges

Big Tariff Refunds Are Coming. How Much and How Soon?

Big Tariff Refunds Are Coming. How Much and How Soon?

Top Tech News

New Spray-on Powder Instantly Seals Life-Threatening Wounds in Battle or During Disasters

New Spray-on Powder Instantly Seals Life-Threatening Wounds in Battle or During Disasters

AI-enhanced stethoscope excels at listening to our hearts

AI-enhanced stethoscope excels at listening to our hearts

Flame-treated sunscreen keeps the zinc but cuts the smeary white look

Flame-treated sunscreen keeps the zinc but cuts the smeary white look

Display hub adds three more screens powered through single USB port

Display hub adds three more screens powered through single USB port

We Finally Know How Fast The Tesla Semi Will Charge: Very, Very Fast

We Finally Know How Fast The Tesla Semi Will Charge: Very, Very Fast

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

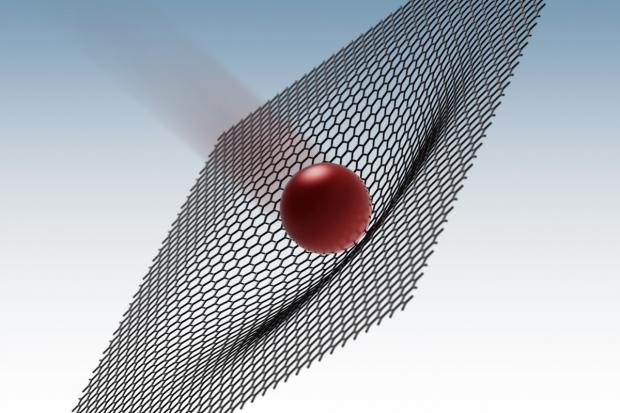

"Graphene armor" protects perovskite solar cells from damage

In just 10 years or so, perovskite solar cells have advanced so fast that they've more or less caught up to silicon's several-decade head start, reaching efficiencies of around 20 percent. But the advantage is that perovskite is cheaper and easier to produce in bulk, and it can be printed or sprayed directly onto surfaces.

But there's always a catch, and in this case that's stability. Perovskite is vulnerable to being degraded by ions coming from the metal oxide electrodes in the solar cell. But now engineers at Ulsan National Institute of Science and technology (UNIST) in South Korea have found a way to protect the perovskite, and the secret ingredient is everyone's favorite wonder material, graphene.

Graphene is a two-dimensional lattice of carbon atoms, which is transparent, super strong and electrically conductive. That makes it perfect for this purpose – it allows photons of light and electrons to pass through, but blocks metal ions.

The team's new system is made using what they call a graphene copper grid-embedded polyimide (GCEP), which sits between the metal electrode and the perovskite. This layer allows sunlight to pass through to the perovskite to convert the energy to electrons, which are then passed back through the GCEP to the metal electrode and out to be stored and used.

In tests, the researchers showed that the new design was almost as efficient as the regular kind. Solar cells protected by the "graphene armor" had power conversion efficiencies of 16.4 percent, compared to 17.5 percent for those without. It managed to maintain that for long periods too, retaining more than 97.5 percent of that efficiency after 1,000 hours.

Iran & Epstein Fallout

Iran & Epstein Fallout