Breaking News

Sunday FULL SHOW: Newly Released & Verified Epstein Files Confirm Globalists Engaged...

Sunday FULL SHOW: Newly Released & Verified Epstein Files Confirm Globalists Engaged...

Fans Bash Bad Bunny's 'Boring' Super Bowl Halftime Show, Slam Spanish Language Performan

Fans Bash Bad Bunny's 'Boring' Super Bowl Halftime Show, Slam Spanish Language Performan

Trump Admin Refuses To Comply With Immigration Court Order

Trump Admin Refuses To Comply With Immigration Court Order

U.S. Government Takes Control of $400M in Bitcoin, Assets Tied to Helix Mixer

U.S. Government Takes Control of $400M in Bitcoin, Assets Tied to Helix Mixer

Top Tech News

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

Study Shows Vaporizing E-Waste Makes it Easy to Recover Precious Metals at 13-Times Lower Costs

Study Shows Vaporizing E-Waste Makes it Easy to Recover Precious Metals at 13-Times Lower Costs

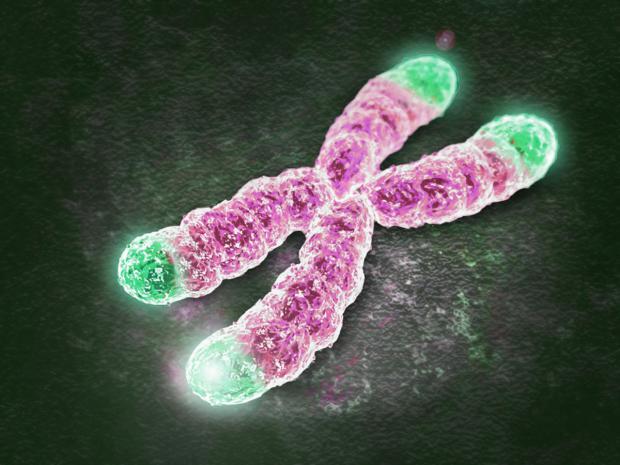

New evidence strengthens link between telomere length, aging and cancer

Now a new study has found an intriguing piece of evidence supporting this hypothesis in genomes from several families that seem to be particularly prone to cancer.

In a way, our cells have a pre-determined number of divisions in their lifetime – around 50. That limit is dictated by our telomeres, small repeating segments of "junk" DNA that form caps on the ends of our chromosomes. These act like a buffer protecting the important DNA in the chromosomes from damage when a cell divides, but a little piece of the telomere is lost each time.

Eventually that damage adds up and the telomeres shorten to the point that the cell stops dividing. This contributes to the symptoms of aging that we're all too familiar with.

In theory, lengthening our telomeres or preventing them from shrinking should help slow the aging process, or even reverse it. Indeed, plenty of research is investigating this angle. But there's a nasty potential downside to doing so – cancer.

Cancer cells are effectively immortal, in the sense that they never stop dividing. It appears that having telomeres of a set length is an evolutionary defense mechanism to prevent that kind of runaway growth. And the new study has found more evidence supporting that hypothesis.

Researchers at the Rockefeller University and the Radboud University Medical Center studied the genomes of several Dutch families that appeared to be quite cancer-prone. Common among these patients were mutations in a gene called TINF2, which codes for a protein previously linked to telomere length.

So the team used CRISPR to engineer human cells with the same mutations, and found that they had much longer telomeres than usual. When the scientists checked the patients themselves, these little caps were also found to be particularly long.

Smart dust technology...

Smart dust technology...