Breaking News

Silver up over $2.26... Today! $71.24 (and Gold close to $4500)

Silver up over $2.26... Today! $71.24 (and Gold close to $4500)

GARLAND FAVORITO: More and more fraud from the 2020 election in Fulton County, Georgia...

GARLAND FAVORITO: More and more fraud from the 2020 election in Fulton County, Georgia...

Rep. Matt Gaetz tells Tucker Carlson that agents of the Israeli govt tried to blackmail his...

Rep. Matt Gaetz tells Tucker Carlson that agents of the Israeli govt tried to blackmail his...

Trump: We need Greenland for national security… you have Russian and Chinese ships all over...

Trump: We need Greenland for national security… you have Russian and Chinese ships all over...

Top Tech News

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

A microbial cleanup for glyphosate just earned a patent. Here's why that matters

A microbial cleanup for glyphosate just earned a patent. Here's why that matters

Japan Breaks Internet Speed Record with 5 Million Times Faster Data Transfer

Japan Breaks Internet Speed Record with 5 Million Times Faster Data Transfer

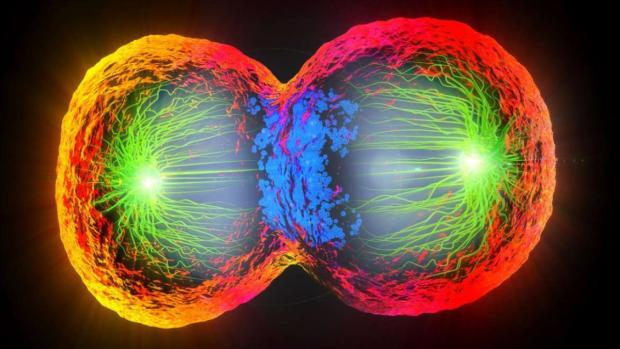

Synthetic organism undergoes cell division in breakthrough study

This breakthrough could lead to designer cells that can produce useful chemicals on demand or treat disease from inside the body.

This new study, by scientists from the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and MIT, builds on over a decade's work in creating synthetic lifeforms. In 2010 a JCVI team created the world's first cell with a synthetic genome, which they dubbed JCVI-syn1.0.

In 2016, the researchers followed that up with JCVI-syn3.0, a version where the goal was to make the organism as simple as possible. With only 473 genes, it was the simplest living cell ever known – by comparison, an E. coli bacterium has well over 4,000 genes. But perhaps it was too simple, because the cells weren't all that effective at dividing. Rather than uniform shapes and sizes, some of them would form filaments and others wouldn't fully separate.

So, for this newest version, named JCVI-syn3A, the team added 19 genes back into the cell, including seven that are required for regular cell division. And sure enough, the new variant was able to divide properly into uniform orbs.

The project can help scientists better understand the process of cell division, and joins a few other breakthroughs in synthetic and semi-synthetic organisms in recent years. In 2012 a team produced the first synthetic cell membrane. In 2017 scientists engineered extra DNA "letters" into the genetic code of a semisynthetic organism – and a few months later it produced an entirely novel protein.