Breaking News

BREAKING: Assault Weapons Ban Just Passed For 2026 : 10 Years Prison Who Own This!

BREAKING: Assault Weapons Ban Just Passed For 2026 : 10 Years Prison Who Own This!

Zelensky To Trump: 'Give Me 50 Year Security Guarantee...And More Money!'

Zelensky To Trump: 'Give Me 50 Year Security Guarantee...And More Money!'

I've Never Seen A USB-C Charger This Good!

I've Never Seen A USB-C Charger This Good!

China Just Broke The Silver Market

China Just Broke The Silver Market

Top Tech News

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

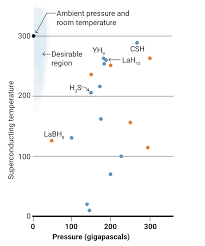

Progress to Practical Room Temperature Superconductors

Theorists have predicted other hydride compounds which could work at lower pressures. There is race to find versions stable at ambient pressure and room temperature.

In 2004, Ashcroft suggested that adding other elements to hydrogen might add a "chemical precompression," stabilizing the hydrogen lattice at lower pressures. The race was on to make superconducting hydrides. In 2015, researchers including Mikhail Eremets, a physicist at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, reported in Nature that a mix of sulfur and hydrogen superconducted at 203 K when pressurized to 155 GPa. Over the next 3 years, Eremets and others boosted the Tc as high as 250 K in hydrides containing the heavy metal lanthanum. Then came Dias's CSH compound, reported late last year in Nature, which superconducts at 287 K—or 14°C, the temperature of a wine cellar—under 267 GPa of pressure, followed by an yttrium hydride that superconducts at nearly as warm a temperature, announced by multiple groups this year.