Breaking News

Iran partially closes Strait of Hormuz, a vital oil choke point, as Tehran holds talks with U.S.

Iran partially closes Strait of Hormuz, a vital oil choke point, as Tehran holds talks with U.S.

Lindsey Graham: 'US Soldiers Could Be Hit In War With Iran...But It's Worth It.'

Lindsey Graham: 'US Soldiers Could Be Hit In War With Iran...But It's Worth It.'

It Begins: Mamdani Plans First NYC Property Tax Hike In Decades To Plug $5 Billion Hole

It Begins: Mamdani Plans First NYC Property Tax Hike In Decades To Plug $5 Billion Hole

SpaceX Enters Secretive Pentagon Contest To Build Voice-Controlled Drone Swarm Tech: Report

SpaceX Enters Secretive Pentagon Contest To Build Voice-Controlled Drone Swarm Tech: Report

Top Tech News

New Spray-on Powder Instantly Seals Life-Threatening Wounds in Battle or During Disasters

New Spray-on Powder Instantly Seals Life-Threatening Wounds in Battle or During Disasters

AI-enhanced stethoscope excels at listening to our hearts

AI-enhanced stethoscope excels at listening to our hearts

Flame-treated sunscreen keeps the zinc but cuts the smeary white look

Flame-treated sunscreen keeps the zinc but cuts the smeary white look

Display hub adds three more screens powered through single USB port

Display hub adds three more screens powered through single USB port

We Finally Know How Fast The Tesla Semi Will Charge: Very, Very Fast

We Finally Know How Fast The Tesla Semi Will Charge: Very, Very Fast

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

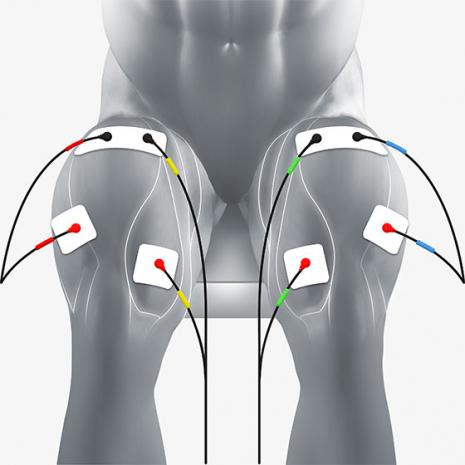

Washable conductive clothing monitors muscle activity

Although traditional electrodes do provide accurate readings, they can be both expensive and uncomfortable, plus they may fall off as the wearer moves around – the latter is definitely an issue if you're trying to monitor an athlete's performance.

Seeking a cheaper, comfier and more reliable alternative, a team led by the University of Utah's Prof. Huanan Zhang started by depositing a microscopic layer of silver onto ordinary cotton/polyester-blend fabric.

Although silver is electrically conductive, it can also be toxic to human skin. For that reason, the team added a similarly thin and flexible layer of gold to the silver. Doing so not only kept the silver from contacting the wearer directly, but it also increased the material's overall conductivity. And while a thicker layer of nothing but gold would also work, combining it with less-expensive silver helps keep costs down below those of conventional electrodes.

In a test of the technology, the silver/gold coating was applied to select areas of a compression sleeve. That sleeve was then placed on a volunteer's forearm, plus electrical wires were run from the coated areas of the garment to a portable electromyography device.

When the person subsequently performed different actions, the sleeve accurately detected the electrical signals produced by their forearm muscles as they contracted. Additionally, the coated areas retained their functionality after the sleeve had gone through 15 wash cycles in an ordinary washing machine.