Breaking News

How Epstein Hijacked Bitcoin with Aaron Day

How Epstein Hijacked Bitcoin with Aaron Day

The Federal Reserve is planned to inject $16 billion into the economy this week...

The Federal Reserve is planned to inject $16 billion into the economy this week...

Dr. Rhonda Patrick: Fasting, Creatine, Brain Performance & Longevity Breakthroughs | PBD #740

Dr. Rhonda Patrick: Fasting, Creatine, Brain Performance & Longevity Breakthroughs | PBD #740

HIGH ALERT! Americans Will Die for Israel's Evil War with Iran | Redacted w Clayton Morris

HIGH ALERT! Americans Will Die for Israel's Evil War with Iran | Redacted w Clayton Morris

Top Tech News

US particle accelerators turn nuclear waste into electricity, cut radioactive life by 99.7%

US particle accelerators turn nuclear waste into electricity, cut radioactive life by 99.7%

Blast Them: A Rutgers Scientist Uses Lasers to Kill Weeds

Blast Them: A Rutgers Scientist Uses Lasers to Kill Weeds

H100 GPUs that cost $40,000 new are now selling for around $6,000 on eBay, an 85% drop.

H100 GPUs that cost $40,000 new are now selling for around $6,000 on eBay, an 85% drop.

We finally know exactly why spider silk is stronger than steel.

We finally know exactly why spider silk is stronger than steel.

She ran out of options at 12. Then her own cells came back to save her.

She ran out of options at 12. Then her own cells came back to save her.

A cardiovascular revolution is silently unfolding in cardiac intervention labs.

A cardiovascular revolution is silently unfolding in cardiac intervention labs.

DARPA chooses two to develop insect-size robots for complex jobs like disaster relief...

DARPA chooses two to develop insect-size robots for complex jobs like disaster relief...

Multimaterial 3D printer builds fully functional electric motor from scratch in hours

Multimaterial 3D printer builds fully functional electric motor from scratch in hours

WindRunner: The largest cargo aircraft ever to be built, capable of carrying six Chinooks

WindRunner: The largest cargo aircraft ever to be built, capable of carrying six Chinooks

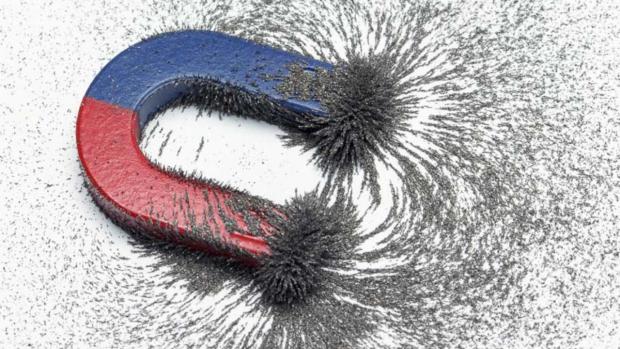

Scientists discover strange new form of magnetism

The most commonly known form of magnetism – the kind that sticks stuff to your fridge – is what's called ferromagnetism, which arises when the spins of all the electrons in a material point in the same direction. But there are other forms such as paramagnetism, a weaker version that occurs when the electron spins point in random directions.

In the new study, the ETH scientists discovered a strange new form of magnetism. The researchers were exploring the magnetic properties of moiré materials, experimental materials made by stacking two-dimensional sheets of molybdenum diselenide and tungsten disulfide. These materials have a lattice structure that can contain electrons.

To find out what type of magnetism these moiré materials possessed, the team first "poured" electrons into them by applying an electrical current and steadily increasing the voltage. Then, to measure its magnetism, they shone a laser at the material and measured how strongly that light was reflected for different polarizations, which can reveal whether the electron spins point in the same direction (indicating ferromagnetism) or random directions (for paramagnetism).

Initially the material exhibited paramagnetism, but as the team added more electrons to the lattice it showed a sudden and unexpected shift, becoming ferromagnetic. Intriguingly, this shift occurred exactly when the lattice filled up past one electron per lattice site, which ruled out the exchange interaction – the usual mechanism that drives ferromagnetism.

"That was striking evidence for a new type of magnetism that cannot be explained by the exchange interaction," said Ataç Imamo?lu, lead author of the study.

RNA Crop Spray: Should We Be Worried?

RNA Crop Spray: Should We Be Worried?