Breaking News

Zone 00: Permaculture for the Inner Landscape (No Land Required)

Zone 00: Permaculture for the Inner Landscape (No Land Required)

Sam Bankman-Fried files for new trial over FTX fraud charges

Sam Bankman-Fried files for new trial over FTX fraud charges

Big Tariff Refunds Are Coming. How Much and How Soon?

Big Tariff Refunds Are Coming. How Much and How Soon?

Top Tech News

New Spray-on Powder Instantly Seals Life-Threatening Wounds in Battle or During Disasters

New Spray-on Powder Instantly Seals Life-Threatening Wounds in Battle or During Disasters

AI-enhanced stethoscope excels at listening to our hearts

AI-enhanced stethoscope excels at listening to our hearts

Flame-treated sunscreen keeps the zinc but cuts the smeary white look

Flame-treated sunscreen keeps the zinc but cuts the smeary white look

Display hub adds three more screens powered through single USB port

Display hub adds three more screens powered through single USB port

We Finally Know How Fast The Tesla Semi Will Charge: Very, Very Fast

We Finally Know How Fast The Tesla Semi Will Charge: Very, Very Fast

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

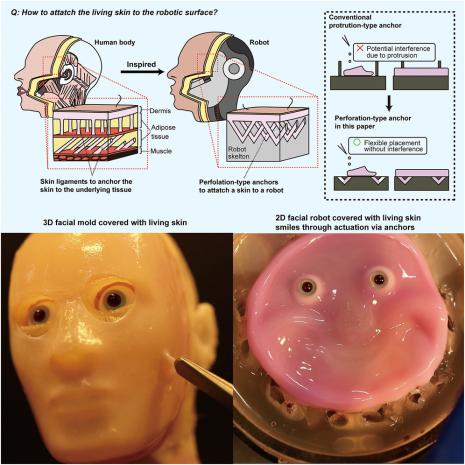

New technique gives robotic faces living human skin

Two years ago, Prof. Shoji Takeuchi and colleagues at the University of Tokyo successfully covered a motorized robotic finger with a bioengineered skin made from live human cells.

It was hoped that this proof-of-concept exercise might pave the way not only for more lifelike android-type robots, but also for bots with self-healing, touch-sensitive coverings. The technology could additionally be used in the testing of cosmetics, and the training of plastic surgeons.

While the skin-covered finger was certainly an impressive achievement, the skin wasn't connected to the underlying digit in any way – it was basically a shrink-to-fit sheath that enveloped the finger. By contrast, natural human skin is connected to the underlying muscle tissue by ligaments.

Among other things, this arrangement allows us to exhibit our various facial expressions. Additionally, by moving along with the underlying tissue, our skin doesn't impede movement by bunching up. For this same reason, it's also less likely to be damaged by getting snagged on external objects.

Scientists have previously attempted to connect bioengineered skin to synthetic surfaces, typically via tiny anchors that protrude up from those surfaces. These pokey anchors detract from the skin's appearance, however, keeping it from looking smooth. They also don't work well on concave surfaces, where they all point in towards the middle.

With such limitations in mind, Takeuchi and his team recently developed a new skin-anchoring system based on tiny V-shaped perforations made in the synthetic surface.

The scientists created a human facial mold that incorporated an array of these perforations, then coated that mold with a gel consisting of collagen and human dermal fibroblasts. The latter are cells which are responsible for producing connective tissue in the skin.

Some of the gel flowed down into the perforations, while the rest stayed on the surface of the mold. After being left to culture for seven days, the gel formed into a covering of human skin that was securely anchored to the mold via the tissue within the perforations.

Iran & Epstein Fallout

Iran & Epstein Fallout