Breaking News

The Self-Sufficiency Myth No One Talks About

The Self-Sufficiency Myth No One Talks About

We Investigated The Maui Fires and The Cover-Up is Worse Than We Thought | Redacted

We Investigated The Maui Fires and The Cover-Up is Worse Than We Thought | Redacted

The Amish Secret to Keeping Pests Out of Your Garden Forever

The Amish Secret to Keeping Pests Out of Your Garden Forever

Scott Ritter: Full-Scale War as Iran Attacks All U.S. Targets

Scott Ritter: Full-Scale War as Iran Attacks All U.S. Targets

Top Tech News

US particle accelerators turn nuclear waste into electricity, cut radioactive life by 99.7%

US particle accelerators turn nuclear waste into electricity, cut radioactive life by 99.7%

Blast Them: A Rutgers Scientist Uses Lasers to Kill Weeds

Blast Them: A Rutgers Scientist Uses Lasers to Kill Weeds

H100 GPUs that cost $40,000 new are now selling for around $6,000 on eBay, an 85% drop.

H100 GPUs that cost $40,000 new are now selling for around $6,000 on eBay, an 85% drop.

We finally know exactly why spider silk is stronger than steel.

We finally know exactly why spider silk is stronger than steel.

She ran out of options at 12. Then her own cells came back to save her.

She ran out of options at 12. Then her own cells came back to save her.

A cardiovascular revolution is silently unfolding in cardiac intervention labs.

A cardiovascular revolution is silently unfolding in cardiac intervention labs.

DARPA chooses two to develop insect-size robots for complex jobs like disaster relief...

DARPA chooses two to develop insect-size robots for complex jobs like disaster relief...

Multimaterial 3D printer builds fully functional electric motor from scratch in hours

Multimaterial 3D printer builds fully functional electric motor from scratch in hours

WindRunner: The largest cargo aircraft ever to be built, capable of carrying six Chinooks

WindRunner: The largest cargo aircraft ever to be built, capable of carrying six Chinooks

A Neuralink Rival Says Its Eye Implant Restored Vision in Blind People

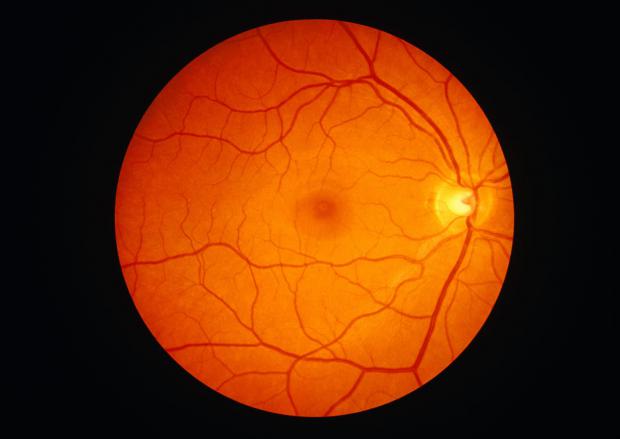

For years, they had been losing their central vision—what allows people to see letters, faces, and details clearly. The light-receiving cells in their eyes had been deteriorating, gradually blurring their sight.

But after receiving an experimental eye implant as part of a clinical trial, some study participants can now see well enough to read from a book, play cards, and fill in a crossword puzzle despite being legally blind. Science Corporation, the California-based brain-computer interface company developing the implant, announced the preliminary results this week.

When Max Hodak, CEO of Science and former president of Neuralink, first saw a video of a blind patient reading while using the implant, he was stunned. It led his company, which he founded in 2021 after leaving Neuralink, to acquire the technology from Pixium Vision earlier this year.

"I don't think anybody in the field has seen videos like that before," he says.

Dubbed the Prima, the implant consists of a 2-mm square chip that is surgically placed under the retina, the backmost part of the eye, in an 80-minute procedure. A pair of glasses with a camera captures visual information and beams patterns of infrared light on the chip, which has 378 light-powered pixels. Acting like a tiny solar panel, the chip converts light to a pattern of electrical stimulation and sends those electrical pulses to the brain. The brain then interprets those signals as images, mimicking the process of natural vision.

There have been other attempts to restore vision by electrically stimulating the retina. Those devices have been able to produce spots of light called phosphenes in people's field of sight—like blips on a radar screen. They're enough to help people perceive people and objects as whitish dots, but it's far from natural vision.

One of these, called the Argus II, was approved for commercial use in Europe in 2011 and in the US in 2013. That implant involved larger electrodes that were placed on top of the retina. Its manufacturer, Second Sight, stopped producing the device in 2020 due to financial difficulties. Neuralink and some others, meanwhile, are aiming to bypass the eye completely and stimulate the brain's visual cortex instead.

Hodak says the Prima differs from other retinal implants in its ability to provide "form vision," or the perception of shapes, patterns, and other visual elements of objects. What users see isn't "normal" vision though. For one, they don't see in color. Rather, they see a processed image with a yellowish tint.

The trial enrolled people with geographic atrophy, an advanced form of age-related macular degeneration, or AMD, that causes gradual loss of central vision. People with the condition still have peripheral vision but have blind spots in their central vision, making it difficult to read, recognize faces, or see in low light.

RNA Crop Spray: Should We Be Worried?

RNA Crop Spray: Should We Be Worried?