Breaking News

The Self-Sufficiency Myth No One Talks About

The Self-Sufficiency Myth No One Talks About

We Investigated The Maui Fires and The Cover-Up is Worse Than We Thought | Redacted

We Investigated The Maui Fires and The Cover-Up is Worse Than We Thought | Redacted

The Amish Secret to Keeping Pests Out of Your Garden Forever

The Amish Secret to Keeping Pests Out of Your Garden Forever

Scott Ritter: Full-Scale War as Iran Attacks All U.S. Targets

Scott Ritter: Full-Scale War as Iran Attacks All U.S. Targets

Top Tech News

US particle accelerators turn nuclear waste into electricity, cut radioactive life by 99.7%

US particle accelerators turn nuclear waste into electricity, cut radioactive life by 99.7%

Blast Them: A Rutgers Scientist Uses Lasers to Kill Weeds

Blast Them: A Rutgers Scientist Uses Lasers to Kill Weeds

H100 GPUs that cost $40,000 new are now selling for around $6,000 on eBay, an 85% drop.

H100 GPUs that cost $40,000 new are now selling for around $6,000 on eBay, an 85% drop.

We finally know exactly why spider silk is stronger than steel.

We finally know exactly why spider silk is stronger than steel.

She ran out of options at 12. Then her own cells came back to save her.

She ran out of options at 12. Then her own cells came back to save her.

A cardiovascular revolution is silently unfolding in cardiac intervention labs.

A cardiovascular revolution is silently unfolding in cardiac intervention labs.

DARPA chooses two to develop insect-size robots for complex jobs like disaster relief...

DARPA chooses two to develop insect-size robots for complex jobs like disaster relief...

Multimaterial 3D printer builds fully functional electric motor from scratch in hours

Multimaterial 3D printer builds fully functional electric motor from scratch in hours

WindRunner: The largest cargo aircraft ever to be built, capable of carrying six Chinooks

WindRunner: The largest cargo aircraft ever to be built, capable of carrying six Chinooks

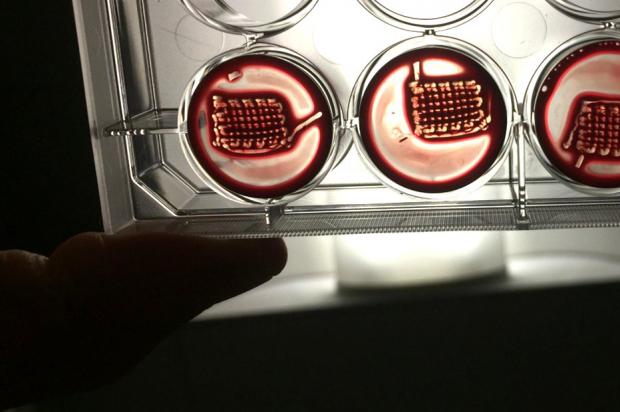

Implants made of your blood could repair broken bone

Now scientists at the University of Nottingham have developed a way to improve on the natural process, making implants created from a patient's own blood to regenerate injuries, even repairing bone.

Bodily tissues can heal small cuts or fractures pretty efficiently. It starts with blood forming a solid structure called a regenerative hematoma (RH), a complex microenvironment that summons key cells, molecules and proteins that regenerate the tissue.

For the new study, the Nottingham researchers created an enhanced version of an RH. Rather than making a completely synthetic one from scratch, they used real blood and boosted its healing properties with peptide amphiphiles (PAs) – synthetic proteins that have different regions that are attracted to water and fats. Essentially, the PAs can build better structures for the hematoma, allowing the healing factors and cells that blood summons to work more effectively.

The team demonstrated that the new materials could perform the usual RH functions, such as recruiting healing cells and generating growth factors, while also being easy to assemble and manipulate. These structures can even be 3D printed into whatever shape is needed for any given patient, using samples of their own blood.

The researchers tested the idea in rats, which had sections of bone surgically removed from their skulls. These new RH structures were grown from their own blood and implanted into the gaps, and sure enough, the injuries showed signs of regeneration. After six weeks, those rats that had received the new RH technique showed up to 62% new bone formation, compared to 50% using a commercially available bone substitute. Untreated control rats saw just 30%.

"The possibility to easily and safely turn people's blood into highly regenerative implants is really exciting," said Dr. Cosimo Ligorio, an author of the study. "Blood is practically free and can be easily obtained from patients in relatively high volumes. Our aim is to establish a toolkit that could be easily accessed and used within a clinical setting to rapidly and safely transform patients' blood into rich, accessible, and tunable regenerative implants."

RNA Crop Spray: Should We Be Worried?

RNA Crop Spray: Should We Be Worried?