Breaking News

US NAVY USELESS: China Activates "Land Route" to Drain Russian Silver

US NAVY USELESS: China Activates "Land Route" to Drain Russian Silver

Lego's next-gen bricks make your creations interactive

Lego's next-gen bricks make your creations interactive

Perhaps We Should Actually Be Focusing On Fixing America

Perhaps We Should Actually Be Focusing On Fixing America

Top Tech News

The First Production All-Solid-State Battery Is Here, And It Promises 5-Minute Charging

The First Production All-Solid-State Battery Is Here, And It Promises 5-Minute Charging

See inside the tech-topia cities billionaires are betting big on developing...

See inside the tech-topia cities billionaires are betting big on developing...

Storage doesn't get much cheaper than this

Storage doesn't get much cheaper than this

Laser weapons go mobile on US Army small vehicles

Laser weapons go mobile on US Army small vehicles

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

A Bitter Pill

Human feces floated in saline solution in a mortar, on a marbled countertop, in a dimly lit kitchen in Burlingame, California. A bottle of ethyl alcohol, an electronic scale, test tubes, and a stack of well-worn pots and pans lay nearby. The stove light illuminated the area as Josiah Zayner crushed the shit with a pestle, creating a brownish-yellow sludge. "I think I can feel something hard in there," he said, laughing. It was probably vegetables — "the body doesn't break them down all the way."

This heralded the beginning of Zayner's bacterial makeover. He was clad in a Wu-Tang Clan T-shirt, jeans, and white socks and sandals. At his feet, James Baxter, Zayner's one-eyed orange cat, rubbed its flank against its owner's legs. The kitchen smelled like an outhouse in a busy campground.

Over the course of the next four days, Zayner would attempt to eradicate the trillions of microbes that lived on and inside his body — organisms that helped him digest food, produce vitamins and enzymes, and protected his body from other, more dangerous bacteria. Ruthlessly and methodically, he would try to render himself into a biological blank slate. Then, he would inoculate himself with a friend's microbes — a procedure he refers to as a "microbiome transplant." Zayner imagines the collection of organisms that live on him — his microbiome — as a suit. As such, it can be worn, mended, and replaced. The suit he was living with, he said, was faulty, leaving him with severe gastrointestinal pain. A new suit could solve all that. "You kind of are who you are, to a certain extent," he said. "But with your bacteria, you can change that."

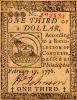

Not Worth a Continental

Not Worth a Continental