Breaking News

Nationwide Tax Competition Heats Up as Missouri Governor Calls for Zero Income Tax

Nationwide Tax Competition Heats Up as Missouri Governor Calls for Zero Income Tax

Matthew McConaughey Trademarks Himself to Fight AI Misuse

Matthew McConaughey Trademarks Himself to Fight AI Misuse

More Americans are surviving cancer - even the deadliest ones

More Americans are surviving cancer - even the deadliest ones

Former CEO of Venezuelan Oil Company CITGO Held Hostage by Nicolas Maduro for Five Years...

Former CEO of Venezuelan Oil Company CITGO Held Hostage by Nicolas Maduro for Five Years...

Top Tech News

Superheat Unveils the H1: A Revolutionary Bitcoin-Mining Water Heater at CES 2026

Superheat Unveils the H1: A Revolutionary Bitcoin-Mining Water Heater at CES 2026

World's most powerful hypergravity machine is 1,900X stronger than Earth

World's most powerful hypergravity machine is 1,900X stronger than Earth

New battery idea gets lots of power out of unusual sulfur chemistry

New battery idea gets lots of power out of unusual sulfur chemistry

Anti-Aging Drug Regrows Knee Cartilage in Major Breakthrough That Could End Knee Replacements

Anti-Aging Drug Regrows Knee Cartilage in Major Breakthrough That Could End Knee Replacements

Scientists say recent advances in Quantum Entanglement...

Scientists say recent advances in Quantum Entanglement...

Solid-State Batteries Are In 'Trailblazer' Mode. What's Holding Them Up?

Solid-State Batteries Are In 'Trailblazer' Mode. What's Holding Them Up?

US Farmers Began Using Chemical Fertilizer After WW2. Comfrey Is a Natural Super Fertilizer

US Farmers Began Using Chemical Fertilizer After WW2. Comfrey Is a Natural Super Fertilizer

Kawasaki's four-legged robot-horse vehicle is going into production

Kawasaki's four-legged robot-horse vehicle is going into production

The First Production All-Solid-State Battery Is Here, And It Promises 5-Minute Charging

The First Production All-Solid-State Battery Is Here, And It Promises 5-Minute Charging

Researchers Develop Molecule That Can Finally Help Stop Arthritis From Wearing Down Joints

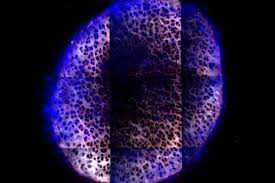

Osteoarthritis, a disease that causes severe joint pain, affects more than 20 million people in the United States. Some drug treatments can help alleviate the pain, but there are no treatments that can reverse or slow the cartilage breakdown associated with the disease.

In an advance that could improve the treatment options available for osteoarthritis, MIT engineers have designed a new material that can administer drugs directly to the cartilage. The material can penetrate deep into the cartilage, delivering drugs that could potentially heal damaged tissue.

"This is a way to get directly to the cells that are experiencing the damage, and introduce different kinds of therapeutics that might change their behavior," says Paula Hammond, head of MIT's Department of Chemical Engineering and the senior author of the study.

In the study, the researchers showed that delivering an experimental drug called insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) with this new material prevented cartilage breakdown much more effectively than injecting the drug into the joint on its own.

Osteoarthritis is a progressive disease that can be caused by a traumatic injury such as tearing a ligament; it can also result from gradual wearing down of cartilage as people age. A smooth connective tissue that protects the joints, cartilage is produced by cells called chondrocytes but is not easily replaced once it is damaged.

Previous studies have shown that IGF-1 can help regenerate cartilage in animals. However, many osteoarthritis drugs that showed promise in animal studies have not performed well in clinical trials.

The MIT team suspected that this was because the drugs were cleared from the joint before they could reach the deep layer of chondrocytes that they were intended to target. To overcome that, they set out to design a material that could penetrate all the way through the cartilage.

The sphere-shaped molecule they came up with contains many branched structures called dendrimers that branch from a central core. The molecule has a positive charge at the tip of each of its branches, which helps it bind to the negatively charged cartilage. Some of those charges can be replaced with a short flexible, water-loving polymer, known as PEG, that can swing around on the surface and partially cover the positive charge. Molecules of IGF-1 are also attached to the surface.

Storage doesn't get much cheaper than this

Storage doesn't get much cheaper than this