Breaking News

Importing Poverty into America: Devolving Our Nation into Stupid

Grand Theft World Podcast 273 | Goys 'R U.S. with Guest Rob Dew

Grand Theft World Podcast 273 | Goys 'R U.S. with Guest Rob Dew

Anchorage was the Receipt: Europe is Paying the Price… and Knows it.

Anchorage was the Receipt: Europe is Paying the Price… and Knows it.

The Slow Epstein Earthquake: The Rupture Between the People and the Elites

The Slow Epstein Earthquake: The Rupture Between the People and the Elites

Top Tech News

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Drone-launching underwater drone hitches a ride on ship and sub hulls

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

Humanoid Robots Get "Brains" As Dual-Use Fears Mount

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Space AI is the Key to the Technological Singularity

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Velocitor X-1 eVTOL could be beating the traffic in just a year

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Starlink smasher? China claims world's best high-powered microwave weapon

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Wood scraps turn 'useless' desert sand into concrete

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

Let's Do a Detailed Review of Zorin -- Is This Good for Ex-Windows Users?

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

The World's First Sodium-Ion Battery EV Is A Winter Range Monster

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

China's CATL 5C Battery Breakthrough will Make Most Combustion Engine Vehicles OBSOLETE

New Research Shows That Gut Microbes May 'Significantly' Slow the Progression of ALS

Scientists are quickly discovering that our gut microbiomes may hold the key to a vast amount of health issues—including ALS.

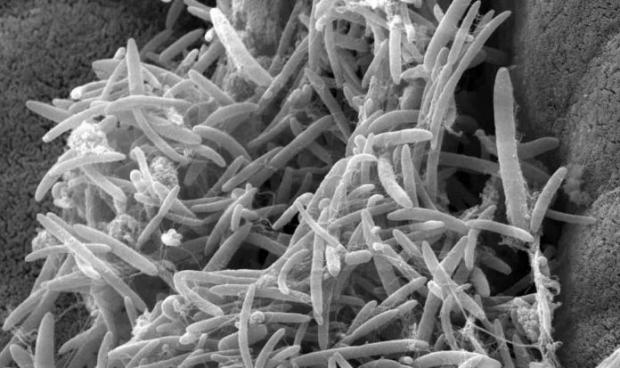

Researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science have shown in mice that intestinal microbes, collectively termed the gut microbiome, may affect the course of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease.

As reported this week in Nature, progression of an ALS-like disease was slowed after the mice received certain strains of gut microbes or substances known to be secreted by these microbes—and results suggest that these findings are likely applicable to human patients with ALS.

"Our long-standing scientific and medical goal is to elucidate the impact of the microbiome on human health and disease, with the brain being a fascinating new frontier," says Professor Eran Elinav of the Immunology Department.

The scientists started out demonstrating in a series of experiments that the symptoms of an ALS-like disease in transgenic mice worsened after these mice were given broad-spectrum antibiotics to wipe out a substantial portion of their microbiome. Additionally, the scientists found that growing these ALS-prone mice in germ-free conditions (in which, by definition, mice carry no microbiome of their own), is exceedingly difficult, as these mice had a hard time surviving in the sterile environment. Together, these results hinted at a potential link between alterations in the microbiome and accelerated disease progression in mice that were genetically susceptible to ALS.

Next, using advanced computational methods, the scientists characterized the composition and function of the microbiome in the ALS-prone mice, comparing them to regular mice. They identified 11 microbial strains that became altered in ALS-prone mice as the disease progressed or even before the mice developed overt ALS symptoms. When the scientists isolated these microbial strains and gave them one by one—in the form of probiotic-like supplements—to ALS-prone mice following antibiotic treatment, some of these strains had a clear negative impact on the ALS-like disease. But one strain, Akkermansia muciniphila, significantly slowed disease progression in the mice and prolonged their survival.

To reveal the mechanism by which Akkermansia may be producing its effect, the scientists examined thousands of small molecules secreted by the gut microbes. They zeroed in on one molecule called nicotinamide (NAM): Its levels in the blood and in the cerebrospinal fluid of ALS-prone mice were reduced following antibiotic treatment and increased after these mice were supplemented with Akkermansia, which was able to secrete this molecule.

To confirm that NAM was indeed a microbiome-secreted molecule that could hinder the course of ALS, the scientists continuously infused the ALS-prone mice with NAM. The clinical condition of these mice improved significantly. A detailed study of gene expression in their brains suggested that NAM improved the functioning of their motor neurons.