Breaking News

4409 -- How Christians were Hoodwinked by the Scofield Bible

4409 -- How Christians were Hoodwinked by the Scofield Bible

Why Do They Hate Thomas Massie

3 MILLION Epstein Pages Released - I Can't Unsee What I Found

3 MILLION Epstein Pages Released - I Can't Unsee What I Found

David Morgan and Mike Adams Talk Silver Demand, Refinery Shortages,...

David Morgan and Mike Adams Talk Silver Demand, Refinery Shortages,...

Top Tech News

How underwater 3D printing could soon transform maritime construction

How underwater 3D printing could soon transform maritime construction

Smart soldering iron packs a camera to show you what you're doing

Smart soldering iron packs a camera to show you what you're doing

Look, no hands: Flying umbrella follows user through the rain

Look, no hands: Flying umbrella follows user through the rain

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

Thorium - THE AGE OF ELECTRICITY

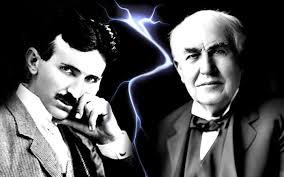

The late 1800s. A time in America of unlimited freedom. A time of the rugged individualist. Tom Edison, deep in his Menlo Park laboratory, creating the Electric Age. Nicola Tesla, the immigrant competitor, with his electric motor and alternating current. It was the Golden Age of America. A time of invention, entrepreneurialism, and genius set free.

At least, that's the popular myth.

But did you ever wonder what happened to those early American electric companies? Where is Edison's company today? Where is Westinghouse's company? In fact, where is any private enterprise electric company?

In 1878, Thomas Edison (and English electrician, Joseph Swan) invented the electrical-resistance-heated, carbon filament, incandescent light bulb. Self-contained, clean and long-burning, the light bulb was the first popular application for electricity.

Edison's goal was to replace gas lighting on city streets. With the help of his young Scottish assistant, Samuel Insull, Edison demonstrated the convenience of his electric light bulbs to the New York City bureaucrats, who granted him exclusive rights to operate a lighting system on Wall Street.

Edison then built the world's first electricity generating and distributing system. His Pearle Street plant went into operation in 1881. The station used one direct current generator and provided 100 Kilowatts, just enough to power 1,200 bulbs. The Electric Age had dawned, but because Edison's plant was powered by burning coal, it was monumentally inefficient.

By 1883, only two years later, electric street lighting was becoming commonplace in American cities. There were more than three hundred such electrical generators in operation around the country — all simple DC dynamos, like Edison's, mostly locally owned, operated by steam engines or water wheels, providing electricity to a few city blocks or to a single factory. Voltage regulation was poor and bulbs often dimmed or burned out. But the electric age had obviously dawned.

These generators became so commonplace that street lighting was soon considered a "public service." Most companies, started as private ventures, were rapidly taken over by the cities — and there were logical reasons for it. There were legal obstacles to stringing wires along public spaces and across property lines. With city bureaucrats easing the way, the wires were installed. Practical DC electric motors were invented and found widespread use in factories, mills, mines and industrial plants of all sorts. Electric motors, supplied by city-run electricity systems, replaced locally owned and operated water wheels, boilers and steam engines for mechanical or shaft power purposes. The electric power industry was changing the face of the nation.

Edison's new goal was to build his first large scale power plant in New York City. He needed money, so he went to J. P. Morgan, and together they founded Edison General Electric Company. They set out to build large, centralized power plants and sell the electricity, not just to businesses, but to the public. There were huge start-up costs — building the largest generators in the world, stringing expensive wire. When Morgan realized his financial return would be too slow to satisfy his investors, he convinced Edison to focus on selling equipment, and leave it to the governments to put up capital.

By 1900, Edison-GE controlled 1,245 power stations around the country. But profits were disappointing. Edison's dream of selling electricity to the public large-scale for a profit just wasn't happening. Demand schedules kept electricity expensive for most people — street lighting drew power only at night — the same hours people wanted lighting for their homes, but GE had to operate all day long. It needed to sell electricity 24 hours a day.

It was streetcars that came to the rescue. They had been invented by Siemens in 1890. By the turn of the century, with GE producing electricity to run them, there were streetcars in 850 American cities. Entrepreneurial progress, right? Unfortunately, this only made the cry that electricity was a "necessary public service," even louder. Consequently, most of the plants that powered street lights street cars became city-owned and buyers of electricity became tax-subsidized customers of Edison General Electric.

Meanwhile, the invention of the induction motor led to the invention of power washing machines (1907), vacuum cleaners (1908) and household refrigerators (1912). A full-scale tech revolution was in play. GE's demand schedules became balanced. But America left the electricity free market behind.

Edison-GE's near-total domination of the electricity market would not last long, however. In 1884, Edison hired a brilliant young Croatian electrical engineer named Nicola Tesla — who had conceived of a better way to generate and distribute electricity: alternating-current. It could generate high and low voltages with ease. It allowed the current to be distributed on small wires, enabling generators to expand their service area.

Tesla not only knew how to power Edison's light bulbs at a distance using thinner, cheaper wire, he had also perfected a simple, rugged, low-cost, efficient A-C (induction) motor that could drive all manner of machinery with little maintenance.

But … Edison didn't want to hear about it.

Edison had thousands of government contracts in the bag. He thought inefficient government subsidized electricity was all he — or the nation — needed. Why change? He already dominated the market. Like bureaucrats do, he thought he could prevent the future from happening. Tesla had to take his business elsewhere.

While Edison was building and collecting DC power stations, Tesla went to George Westinghouse, instead. And at first, progress was slow. In 1886, the first commercial alternating current power system was built. By 1891, Tesla had built the AC induction motor, the Tesla Coil, and the transformer — the fundamental things necessary for the long-distance transmission of electricity.

Westinghouse's Niagara Power Plant was built in 1896, a milestone in the history of U.S. electricity. The Power Plant had 37 megawatt power output, making it several hundreds times more powerful than Edison's Pearle Station. It sent electricity over 25 miles of transmission line at high-voltage (11,000 volts) to Buffalo city — and it was also the world's first large-scale hydro-electric power plant.

But Westinghouse, too, had to partner with city bureaucrats to get the system built.

Today, we tend to believe the early electric companies were created by daring speculators, mavericks, rugged individualists. But that was only partly true. The truth is, electric companies never were 100 percent private, profit-seeking ventures — they were controlled by politicians from the start.

One thing is true, however. The "Roaring Twenties" did indeed roar. It's easy to imagine why people believed in a future of endless prosperity. It was the Age of Electricity. The Age of Aviation. The Age of Radio. The Age of Progress. But the party ended with the banking collapse of 1929.