Breaking News

DRINK 1 CUP Before Bed for a Smaller Waist

Nano-magnets may defeat bone cancer and help you heal

Nano-magnets may defeat bone cancer and help you heal

Dan Bongino Officially Leaves FBI After One-Year Tenure, Says Time at the Bureau Was...

Dan Bongino Officially Leaves FBI After One-Year Tenure, Says Time at the Bureau Was...

WATCH: Maduro Speaks as He's Perp Walked Through DEA Headquarters in New York

WATCH: Maduro Speaks as He's Perp Walked Through DEA Headquarters in New York

Top Tech News

Laser weapons go mobile on US Army small vehicles

Laser weapons go mobile on US Army small vehicles

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

EngineAI T800: Born to Disrupt! #EngineAI #robotics #newtechnology #newproduct

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

This Silicon Anode Breakthrough Could Mark A Turning Point For EV Batteries [Update]

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Travel gadget promises to dry and iron your clothes – totally hands-free

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

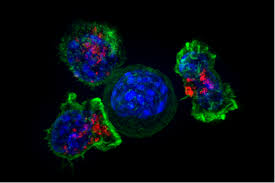

Scientists find powerhouses that fight tumours from within

In recent years doctors have turned to a new treatment for cancer, immunotherapy, which works by leveraging the body's own immune system to fight tumours.

The technique has largely focused on white blood cells called T-cells, which are "trained" to recognise and attack cancer cells.

But the innovative treatment only works well for around 20 percent of patients, and researchers have been trying to understand why some people respond better than others.

Three papers published on Thursday in the journal Nature point the way, identifying a key formation inside some tumours: tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS).