Breaking News

Why are young women attracted to older men? Men, watch and learn!

Why are young women attracted to older men? Men, watch and learn!

Voter Fraud Is About To Explode: ITS BLOWING UP IN THEIR FACES thanks to Trump and Tulsi

Voter Fraud Is About To Explode: ITS BLOWING UP IN THEIR FACES thanks to Trump and Tulsi

Ahead of US-Iran Talks, Netanyahu Tells Cabinet 'Conditions' Could Lead to Regime Change...

Ahead of US-Iran Talks, Netanyahu Tells Cabinet 'Conditions' Could Lead to Regime Change...

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

SpaceX Authorized to Increase High Speed Internet Download Speeds 5X Through 2026

Top Tech News

How underwater 3D printing could soon transform maritime construction

How underwater 3D printing could soon transform maritime construction

Smart soldering iron packs a camera to show you what you're doing

Smart soldering iron packs a camera to show you what you're doing

Look, no hands: Flying umbrella follows user through the rain

Look, no hands: Flying umbrella follows user through the rain

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

Critical Linux Warning: 800,000 Devices Are EXPOSED

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

'Brave New World': IVF Company's Eugenics Tool Lets Couples Pick 'Best' Baby, Di

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

The smartphone just fired a warning shot at the camera industry.

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

A revolutionary breakthrough in dental science is changing how we fight tooth decay

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Docan Energy "Panda": 32kWh for $2,530!

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

Rugged phone with multi-day battery life doubles as a 1080p projector

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

4 Sisters Invent Electric Tractor with Mom and Dad and it's Selling in 5 Countries

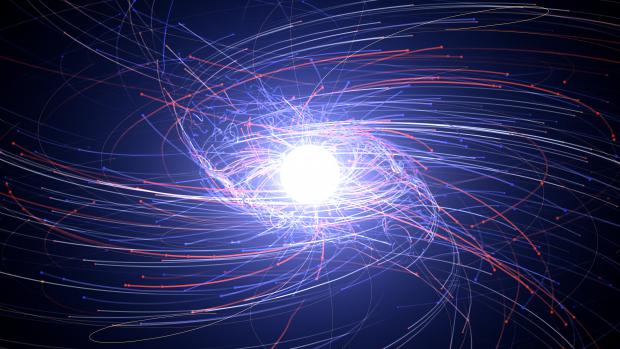

Laser pincers generate antimatter by recreating neutron star conditions

Now a team of physicists has outlined a relatively simple new way to create antimatter, by firing two lasers at each other to reproduce the conditions near a neutron star, converting light into matter and antimatter.

In principle, antimatter sounds simple – it's just like regular matter, except its particles have the opposite charge. That basic difference has some major implications though: if matter and antimatter should ever meet, they will annihilate each other in a burst of energy. In fact, that should have destroyed the universe billions of years ago, but obviously that didn't happen. So how did matter come to dominate? What tipped the scales in its favor? Or, where did all the antimatter go?

Unfortunately, antimatter's scarcity and instability make it difficult to study to help answer those questions. It's naturally produced under extreme conditions, such as lightning strikes, or near black holes and neutron stars, and artificially in huge facilities like the Large Hadron Collider.

But now, researchers have designed a new method that could produce antimatter in smaller labs. While the team hasn't built the device yet, simulations show that the principle is feasible.

The new device involves firing two powerful lasers at a plastic block, one from either side in a pincer motion. This block would be crisscrossed by tiny channels, just micrometers wide. As each laser strikes the target, it accelerates a cloud of electrons in the material and sends them shooting off – until they collide with the cloud of electrons coming the other way from the other laser.