Breaking News

Catherine Fitts: Epstein, CIA Black Budget, the Control Grid, and the Banks' Role in War

Catherine Fitts: Epstein, CIA Black Budget, the Control Grid, and the Banks' Role in War

"It's a disaster": Germans allowed to use oil and gas to heat their homes again

"It's a disaster": Germans allowed to use oil and gas to heat their homes again

Victor Davis Hanson: Trump's Cost-Benefit Analysis For Striking Iran

Victor Davis Hanson: Trump's Cost-Benefit Analysis For Striking Iran

Who is really running the world?

Who is really running the world?

Top Tech News

US particle accelerators turn nuclear waste into electricity, cut radioactive life by 99.7%

US particle accelerators turn nuclear waste into electricity, cut radioactive life by 99.7%

Blast Them: A Rutgers Scientist Uses Lasers to Kill Weeds

Blast Them: A Rutgers Scientist Uses Lasers to Kill Weeds

H100 GPUs that cost $40,000 new are now selling for around $6,000 on eBay, an 85% drop.

H100 GPUs that cost $40,000 new are now selling for around $6,000 on eBay, an 85% drop.

We finally know exactly why spider silk is stronger than steel.

We finally know exactly why spider silk is stronger than steel.

She ran out of options at 12. Then her own cells came back to save her.

She ran out of options at 12. Then her own cells came back to save her.

A cardiovascular revolution is silently unfolding in cardiac intervention labs.

A cardiovascular revolution is silently unfolding in cardiac intervention labs.

DARPA chooses two to develop insect-size robots for complex jobs like disaster relief...

DARPA chooses two to develop insect-size robots for complex jobs like disaster relief...

Multimaterial 3D printer builds fully functional electric motor from scratch in hours

Multimaterial 3D printer builds fully functional electric motor from scratch in hours

WindRunner: The largest cargo aircraft ever to be built, capable of carrying six Chinooks

WindRunner: The largest cargo aircraft ever to be built, capable of carrying six Chinooks

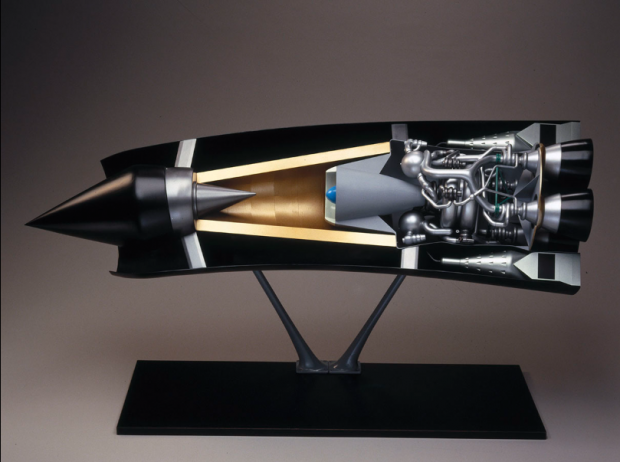

Hypersonic SABRE engine reignited in Invictus Mach 5 spaceplane

Sometimes you have to admire sheer perseverance when it comes to technological innovations.

In 1982, British Aerospace and Rolls-Royce teamed up to develop the Horizontal Take-Off and Landing (HOTOL) spaceplane that was intended to be a single-stage-to-orbit vehicle that could take off and land from a conventional runway and could breathe air for most of its flight to drastically cut down on weight.

The program generated a lot of enthusiasm in aerospace circles and a model was proudly displayed in the Science Museum in London. It even garnered a lot of official support from the British government. However, by 1987, Whitehall decided that the project was "over ambitious" and withdrew funding.

But that didn't stop Alan Bond, John Scott-Scott, and Richard Varvill from going private in 1989 and forming their own company, Reaction Engines Limited, to keep the idea alive and develop the key technologies of HOTOL in a new incarnation.

Concentrating on the company's SABRE technology as well as side projects to attract revenue and investments, Reaction Engines kept going until 2024 thanks to British and American government contracts and heavy investment by BAE Systems. But a cash-flow crisis forced the company into administration and it was broken up.

Now, a group of companies led by Frazer-Nash and including Spirit AeroSystems, Cranfield University, and a number of small-medium enterprises has launched the Invictus program that aims to develop a Mach 5 spaceplane by early 2031 that operates on the edge of space – and which may one day lead to an orbital launch system.

The key to this is an engine that can swap between different modes – sometimes operating like a jet, sometimes like a rocket. On takeoff, the Invictus would take off from a conventional runway like a conventional plane as its engine breathes air to burn its liquid hydrogen fuel, which saves an enormous amount of weight since no on-board oxygen is needed during this phase. As the aircraft approaches the edge of space, it reconfigures itself into a rocket and uses liquid oxygen, though much less than a conventional launcher would.

At the heart of Invictus is the pre-cooler system for the SABRE engine. In a jet engine flying at hypersonic speeds, the incoming air is compressed and heats to a temperature that would quickly melt and destroy any material the engine might be made of. To prevent this, the engine's hydrogen fuel runs through a heat exchanger to chill a liquid helium coolant that flows through a complex network of small tubes in the air inlet. These cool the incoming air from over 1,000 °C (1,832 °F) to ambient temperature in less than 1/20th of a second. The cooled air is then mixed with liquid hydrogen and ignited.

RNA Crop Spray: Should We Be Worried?

RNA Crop Spray: Should We Be Worried?