Breaking News

"Fixing" Your Cummins Diesel . . .

"Fixing" Your Cummins Diesel . . .

SPLC Labels Turning Point USA as a "Hate Group"-Charlie Kirk Responds: "A cheap smear

SPLC Labels Turning Point USA as a "Hate Group"-Charlie Kirk Responds: "A cheap smear

Ukraine Wipes Out Dozens of Russian Nuclear Bombers in Drone Strike Deep Inside Russia...

Ukraine Wipes Out Dozens of Russian Nuclear Bombers in Drone Strike Deep Inside Russia...

Top Tech News

New AI data centers will use the same electricity as 2 million homes

New AI data centers will use the same electricity as 2 million homes

Is All of This Self-Monitoring Making Us Paranoid?

Is All of This Self-Monitoring Making Us Paranoid?

Cavorite X7 makes history with first fan-in-wing transition flight

Cavorite X7 makes history with first fan-in-wing transition flight

Laser-powered fusion experiment more than doubles its power output

Laser-powered fusion experiment more than doubles its power output

Watch: Jetson's One Aircraft Just Competed in the First eVTOL Race

Watch: Jetson's One Aircraft Just Competed in the First eVTOL Race

Cab-less truck glider leaps autonomously between road and rail

Cab-less truck glider leaps autonomously between road and rail

Can Tesla DOJO Chips Pass Nvidia GPUs?

Can Tesla DOJO Chips Pass Nvidia GPUs?

Iron-fortified lumber could be a greener alternative to steel beams

Iron-fortified lumber could be a greener alternative to steel beams

One man, 856 venom hits, and the path to a universal snakebite cure

One man, 856 venom hits, and the path to a universal snakebite cure

Dr. McCullough reveals cancer-fighting drug Big Pharma hopes you never hear about…

Dr. McCullough reveals cancer-fighting drug Big Pharma hopes you never hear about…

When East and West can't meet: Between Leviathan, Behemoth and Mandala

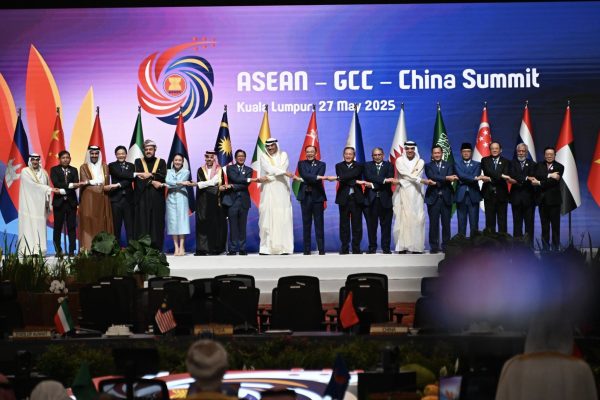

The first ever ASEAN-China-GCC trilateral summit earlier this week in Malaysia – with 17 Global South nations at the table – was a de facto celebration of the New Silk Road spirit.

Malaysian Prime Minister and current ASEAN chair Anwar Ibrahim summed it all up: "From the ancient Silk Road to the vibrant maritime networks of Southeast Asia to modern trade corridors, our peoples have long connected through commerce, culture, and the sharing of ideas."

That inspires a lot of reflection. Let's try a first, succint approach matching East and West – and what divides them – guided by an extraordinary study, La Mediterranee Asiatique: XVI-XXI Siecle, by CNRS research director Francois Gipouloux, also a specialist in the Chinese economy.

The European tradition is far from monolithic – and it's only part of the picture – when it comes to global perceptions about political philosophy and the conception of the State. There are stark differences even when referred to Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau.

The heart of the matter used to be the land/sea opposition. For Carl Schmitt, land/sea relates to friend/enemy – the matrix of politics – providing a key interpretation of world history, yet one among many.

It's on "continental" Europe – to borrow the Anglo terminology –, mostly in France and Prussia, and not in England, that the Hobbesian concept of the State materialized. Britain became a world power thanks to its navy and trade, eschewing the characteristic institutions of the state such as a written constitution and a legislative codification of law.

Anglo-Saxon international law in fact voided the continental conception of the State and also war. According to Schmitt, it developed its own concepts of "war" and "enemy" out of maritime and trade conflicts which did not make a distinction between combatants and non-combatants (when it comes to its lasting legacy, think "the war on terror").

My war is Just, because I said so

The opposition then solidified between the right to wage war on land – war is "just" if it happens between sovereign states, via regular armies, and sparing civilians – and waging war on sea, which does not imply a state-to-state relation. What mattered was attacking the trade and the economy of the enemy. And methods of total war were directed against either combatants or non-combatants.

That led to a new Western concept of "Just War" and international law: when the enemy is turned into a criminal, juridical and moral equality between belligerents is shattered. That's the perverse logic behind psycho-pathological genocidals legitimizing the destruction of Palestine.

These differences in the formulation of law came out of two different conceptions of space: closed, overland – featuring sovereign states, territorially delimitated – and open, over the seas – a unique space, unlimited, free of every state control, where primacy is about securing communication links. The British did not think about space in terms of territory, but of routes of communication, just like the Portuguese and the Dutch before them.

Schmitt identifies in the State an entity linked to land and territory. So, as startling as it seems, it's Behemoth, the terrestrial animal of the Old Testament, and not the marine monster Leviathan that should have been chosen by Hobbes as a symbol of the State.

In the development of the West, three institutional forms – equally viable – were in competition: Leagues of Cities – like the Hanseatic Legue; City-States – especially in Italy; and the Nation-State, especially in France.

Elon Musk: Bono Is A Retard

Elon Musk: Bono Is A Retard