Breaking News

Rising Male Infertility A Catastrophe Waiting to Happen

Rising Male Infertility A Catastrophe Waiting to Happen

EU is Broke & Rejects Peace Since They Would Have to Return Russian Money

EU is Broke & Rejects Peace Since They Would Have to Return Russian Money

The Illusion of Democracy: The "Iron Law of Oligarchy"

The Illusion of Democracy: The "Iron Law of Oligarchy"

Top Tech News

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Perfect Aircrete, Kitchen Ingredients.

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Futuristic pixel-raising display lets you feel what's onscreen

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

Cutting-Edge Facility Generates Pure Water and Hydrogen Fuel from Seawater for Mere Pennies

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

This tiny dev board is packed with features for ambitious makers

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Scientists Discover Gel to Regrow Tooth Enamel

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Vitamin C and Dandelion Root Killing Cancer Cells -- as Former CDC Director Calls for COVID-19...

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

Galactic Brain: US firm plans space-based data centers, power grid to challenge China

A microbial cleanup for glyphosate just earned a patent. Here's why that matters

A microbial cleanup for glyphosate just earned a patent. Here's why that matters

Japan Breaks Internet Speed Record with 5 Million Times Faster Data Transfer

Japan Breaks Internet Speed Record with 5 Million Times Faster Data Transfer

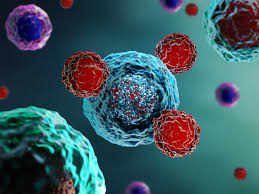

Cancer-Fighting Cells Engineered Inside Patients' Bodies Rather Than Laboratory for the First Ti

If standardized, such an advancement would allow for one of the most successful non-chemo cancer treatments to be done both faster and cheaper.

CAR T-cell therapy involves retrieving a patient's immune system component called a T-cell and using a virus to genetically add the CAR, or chimeric antigen receptor, to it. This process is done in a lab—typically outside the hospital where the patient is being treated—before the cells are shipped back for transplant.

The alteration allows T-cells to home in on cancer cells directly by penetrating the biological stealth capabilities tumors have, but is also expensive and laborious. If, scientists have considered in the last decade, the process could be done inside the body, it would save lives that are sometimes lost waiting out the month-or-so-long process it takes to alter the T-cells in the lab.

That's exactly what's been established in a pair of recent trials, the results of which were just presented at the American Society of Hematology's (ASH) annual meeting.

In the team's first trial in July, 4 patients with multiple myeloma, a kind of blood cancer, had their T-cells engineered in vivo with the CAR gene. They produced the altered cells, which successfully attacked the tumors in their bone marrow.

2 of the patients seemed to be cured, with the cancer cells no longer detectable in their bone marrow, and a tell-tale circulating blood protein also absent from their bodies. 2 others didn't benefit to that extent, but appeared to be in remission after 5 months.

"The question is no longer can you really do this," Yvonne Chen, a cancer immunotherapy researcher at UCLA, told Science News. "The question now is can you reach the level of efficacy that's expected and will the safety profile meet the target."

On the question of safety, the patients suffered from significant side effects, likely due to the effects of the deactivated virus used to reprogram their T-cells, which has been known to trigger flu-like symptoms that have even been fatal on occasion with the lab-based CAR T-cell method.

The Gathering Storm

The Gathering Storm Advanced Propulsion Resources Part 1 of 2

Advanced Propulsion Resources Part 1 of 2